Understanding Trauma (part 3 of 3)

Responding with Compassion in the Local Church; and "Societal PTSD"

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

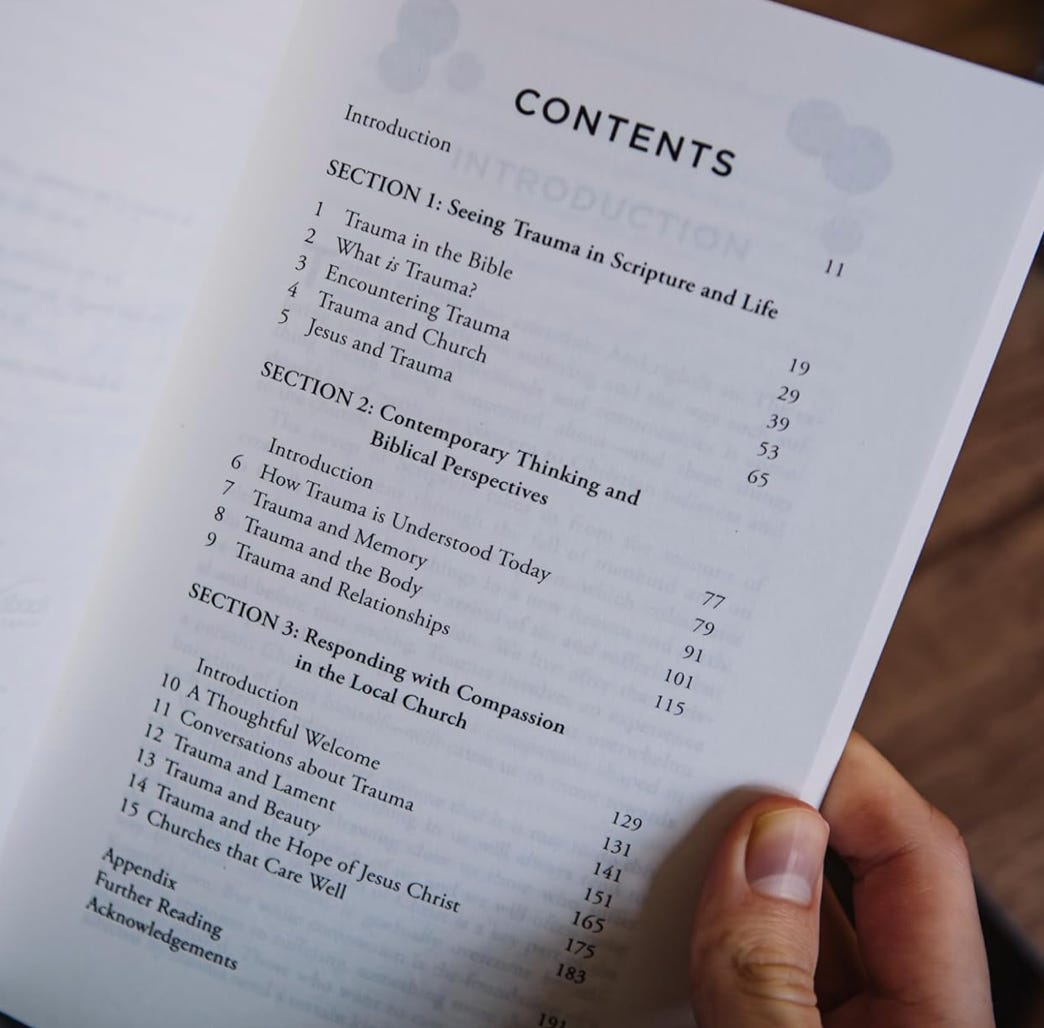

This is the third post in a three-part series on the recently published book Understanding Trauma by Dr Steve Midgley, a qualified psychiatrist who became a pastor and who is now Executive Director of Biblical Counselling UK.

Both part 1, subtitled Seeing Trauma in Scripture and Life, and part 2, subtitled Contemporary Thinking and Biblical Perspectives, provide important context for this article.

Section 3: Responding with Compassion in the Local Church

Introduction to Section 3

In the introduction to Section 3, Midgley notes (p129) that, for churches, trauma is not just an academic interest:

We [as Christians and churches] want to be better equipped in order to welcome and support those who are struggling.

And he is clear about his aim in writing Understanding Trauma:

This book is not intended to be a trauma-recovery guide. Nor is it designed to equip people for any kind of trauma counselling. Some believers will want to develop the experience and skill to engage in care at that level, but for most of us, our ambitions will be much more modest. We simply want to better understand people who have experienced trauma so that we can be good friends and can provide wise pastoral care. We want to know how to speak wisely and avoid clumsy missteps.

And the chapters in the third and final section of the book are written to provide pointers to what those wise and godly conversations might look like and:

…to help us overcome feelings of inadequacy and ignorance that can leave us fearful of saying anything at all.

Chapter 10: A Thoughtful Welcome

Midgley begins Chapter 10 by explaining the distinction between a mere welcome to church and what he calls “a thoughtful welcome”, which, for someone who has suffered trauma, can be very important.

He discusses (1) what a general awareness of the category of trauma looks like, and some of the ways in which it can impact a person. He notes (p133) that:

However much we might wish it were otherwise, people arriving at a church for the first time do often find it difficult and threatening. This is more so for someone who isn’t a Christian and more so again for someone who has experienced trauma.

And adds that:

Every church member is called to bring an attitude of grace towards those who, for whatever reason, find themselves on the margins. The way a church responds to those who struggle to fit in is one measure of the extent to which a gospel culture has been established.

He then considers (2) responsiveness to less common behaviours and requests, recognising (p134) that:

Someone affected by trauma will often find fitting in with the normal conventions of church difficult… unexceptional aspects of church can become incredibly demanding and difficult situations to navigate.

And gives several practical examples.

Finally (3) he emphasises the importance of preachers who are alert to the impact their words may have. He cites Matthew 12:20, which quotes Isaiah 42:3, to make the case (p136) that:

Those experiencing the aftermath of severe suffering can… be considered as bruised reeds, fragile and easily broken.

He has the following suggestions for those charged with preaching:

begin by assuming that someone with an experience of severe suffering may well be present

identify aspects of [the] sermon that may be difficult for some people

make it clear at the start of a church service when a Bible reading and sermon are going to be grappling with a difficult topic or incident

beware remarks about passages that describe severe suffering, which might sound witty to some (including the preacher) but insensitive to others

I have sometimes reflected on the fact that, in any large congregation, there will be people present for whom the past week has been among the best they have ever known, and people present for whom the past week has been among the worst they have ever known.

Chapter 11: Conversations about Trauma

Midgley begins Chapter 11 by pointing out (p141) two mistakes that churches can make in responding to those affected by trauma:

to find the whole area so confusing and troubling that they do nothing… [thinking of it as] “specialist territory” which must only be attempted by experts… [which] can leave people who have experience trauma feeling both ignored and neglected [not least given that] many of those affected will not have access to experts

to believe ourselves capable of doing anything and everything that might be needed to care for someone with trauma

He then turns to discuss four spectrums (p142ff):

1. The severity of impact — where the severity of the event a person has experienced is not a reliable guide to the impact it may have

2. Complexity of the trauma — in the context of protracted suffering, and particularly that experienced from an early age

3. Experience in relation to trauma — different levels of familiarity

4. Role of those offering support — a person offering support can perform one of multiple roles

And seven pointers for beneficial conversations (p144ff), noting that God promises (James 1:5) to give wisdom to those who ask for it:

1. Talk about talking — clarifying what someone wants: “Does it help to talk…? Or is it too difficult?”

That second question can be important. I remember being taught in a culture awareness course at work how some people, particularly in certain parts of the world, find it difficult to answer, “No.”

2. Notice ongoing issues — sometimes trauma is a present and ongoing experience rather than one that concerns an event in the past

3. Get an overview of their experience of trauma — a wise approach being something like: “Do you feel able to give me just a broad picture of what it is that happened? [Or should we wait until another time?]”

4. Consider whether others should be involved — which does not mean withdrawing support; it’s not helpful to think of this in terms of “referring someone on”

5. Listen and witness — when we see someone struggling because of what they have suffered, we naturally want to make things better… but if this leads us to start offering “solutions”, we are likely to misstep… simple and quick solutions for trauma are rarely available

I was particularly struck by this comment (p148)…

Something very significant happens when a story is witnessed and heard, perhaps for the very first time. It reflects enormous courage on the part of the victim of trauma…

…which reminded me of the need to work hard at listening carefully and perhaps even to remain silent for a while (cf. Job 2:12-13) before responding.

6. Expand church connections — it is important to work out which other people are or could be involved in providing support

7. Involve a person in church life — the impact on a person’s sense of self may mean that roles and responsibilities which were once commonplace now seem impossible

Chapter 12: Trauma and Lament

Midgley opens this chapter by noting (p151) that:

Until relatively recently, the biblical practice of lament has been notable by its absence from the lives both of Christians and most churches.

And that:

The relevance of the practice of lament to the experience of trauma is obvious. Lament allows a person to do two critical things: to express the pain and bewilderment of suffering, and to do so in a way that maintains an orientation toward God… The capacity to express pain in God’s presence without abandoning trust in his goodness is critical.

He observes (p152) that:

When trauma raises questions about the goodness of God, lament helps a person wrestle with two realities… [i] their experience of sufferings — something terrible has happened to them… [and] [ii] the goodness that still exists in the world and, still more importantly, the goodness of God.

And he commends the use of the psalms of lament, as discussed in Mark Vroegop’s book Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy…

…which sets out a framework that has helped many engage with the psalms of lament for the first time:

1. Turn — turning to God, noting that, while a psalm of lament typically begins in struggle and complaint before moving on to hope and trust, in Psalm 88 — the deepest and darkest of all the laments — there is no transition

2. Complain — a prominent feature of lament psalms such as Psalm 10, Psalm 74 and Psalm 1371

3. Ask — as part of the process of lament, there can be a bridge from complaint to bold requests, in relation to e.g. justice, security, community and honour

4. Trust — this journey towards trust can be taken either by a whole community or by a single individual; in either case, the communal aspect of lament is important in order that the trauma might be “witnessed”, i.e. a community both sees what has happened and names it… (Emphasis added)

In the context of recent years, I was particularly struck by those italicised words in the last part of the framework. And also by these two statements:

This journey towards trust is generally slow, but the psalms of lament are excellent travelling companions.

And:

The transition from despair to trust is often abrupt.

The latter reminded me of the notion that sometimes things happen very slowly, and then all at once…

But in relation to all of the above it is important to remember that, as Midgley points out (p156):

Wrestling with the experience of severe suffering is neither easy nor speedy

With the above framework in mind, Midgley contends (p159) that:

If you are seeking to walk with someone who is suffering from trauma, then one way of loving them well and wisely is to help them lament… the first and simplest way [being] just to introduce the possibility.

He also discusses lament in a small group or corporate setting, where of course the format would be rather different.

Despite having been to thousands of church (and chapel) services in my lifetime, I can remember very few (if any) instances of what might be described as corporate lament. Perhaps the closest is the brief-and-now-rarely-used, “We acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness” from the 1928 Book of Common Prayer.

But I do wonder whether that might change in the coming years as more people begin to understand the reality of what has been — and still is — happening.

Chapter 13: Trauma and Beauty

Midgley opens this chapter by acknowledging (p165) that:

The theme of beauty may not, at first sight, seem the most obvious avenue to explore in relation to the experience of trauma.

But he contends that:

…it proves to be not only a powerful lens through which to view the experience of trauma but also a biblical one…

He recognises that:

Trauma is ugly.

And that:

Whenever trauma enters a life, ugliness intrudes with it.

He goes on to explain, citing the early chapters of Genesis, how:

…the origin of this ugliness is found in the distorting and ruinous impacts of sin

And that:

If ugliness involves distortion and disruption such that things fall apart, beauty proves to be the opposite.

He cites Psalm 27:4-5…

One thing I ask from the Lord, this only do I seek: that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life, to gaze on the beauty of the Lord and to seek him in his temple. For in the day of trouble he will keep me safe in his dwelling; he will hide me in the shelter of his sacred tent and set me high upon a rock.

…which he contends:

…captures the deepest longing of all of us, whether we realise it or not — to see beauty by seeing the face of God himself.

Those are indeed striking verses, although I think they do have to be held in tension with Isaiah 53 which says of the suffering servant, i.e. God in the person of his Son:

He grew up before him like a tender shoot, and like a root out of dry ground. He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him. He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, and familiar with pain. Like one from whom people hide their faces he was despised, and we held him in low esteem.

While even the feet of those who bring good news are described as beautiful, the Bible states that God’s servant — Jesus Christ — had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him.

But it is hard to argue with Midgley’s contention (p168) that:

…the gospel message [of the bringers of good news] reflects the perfect beauty of God’s character.

That:

Redemption is beautiful. Grace is beautiful. Heaven will be eternally beautiful.

And that:

…for those whose lives have been marred by the ugliness of trauma, this promise of beauty can be life-changing.

He applies Psalm 27 at some length in this context, and points to the promise of John’s vision at the end of Revelation:

I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband.

In the context of a discussion on trauma recovery, he points out (p170) that:

…although the cross [i.e. Jesus’ crucifixion] seems appallingly ugly, it is, in fact, beauty itself: the beauty of a redeeming death that demonstrates to us the boundless love of God.

And adds that:

Through an encounter with the redeeming work of Jesus, the ugliness of trauma can begin to be undone.

Midgley then turns to the theme of restoration by beauty, citing passages such as Matthew 11:4-6:

Go back and report to John what you hear and see: the blind receive sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the good news is proclaimed to the poor.

Noting that:

Jesus brings the beauty of a restored humanity.

He ends the chapter (p172) with some suggestions as to how:

…themes of ugliness and beauty might guide the support and care we offer to those who have experienced trauma:

the need to listen — to acknowledge the ugliness of what has happened to someone…

[the use of] passages that describe and declare the beauty of the Lord [and] can lift a person’s eyes… to gaze upon their Saviour — e.g. Revelation 1:12-16, Job 38-39, and various psalms

the focusing on the beauty of God in the context of church gatherings

the finding of beauty in giving ourselves in service to others

I am also inclined to think, not least in the context of Philippians 4:8 — “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable — if anything is excellent or praiseworthy — think about such things”2 — that thinking about and telling the truth is intrinsically linked with beauty and the one who is truth (cf. John 14:6, Psalm 31:53).

Chapter 14: Trauma and the Hope of Jesus Christ

In Chapter 14, Midgley builds on the beauty and lament themes of the previous two chapters (p175):

In the ugliness of trauma, beauty intrudes — and that beauty is most fully and wonderfully encountered in the person of Jesus Christ. As we lament, we begin to hope — and Jesus provides the ultimate hope to which lament points.

On the subject of hope, I am reminded of what the apostle Paul writes to Christians in Romans 5:1-4:

Therefore, since we have been justified through faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have gained access by faith into this grace in which we now stand. And we boast in the hope of the glory of God. Not only so, but we also glory in our sufferings, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope.

Midgley cites two things to note as we consider how the redemption that Christ brings helps us to walk alongside those struggling with trauma:

First of all, we can joyfully and confidently proclaim that whatever trauma a person may face, Christ provides the redeeming love they need. Yet second, we must do this in a way that does not end up implying that there is anything simple or easy about… living in response to the redemption that Christ provides…

Trauma’s impact is not quickly resolved… But nevertheless, it is to Jesus that we need to bring our friends who are suffering.

Midgley explains, in a manner reminiscent of a well-constructed three point sermon, that:

[i] Christ knows our suffering — citing Hebrews 2:14-15:

Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death — that is, the devil — and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death.

I remember citing that very passage when I wrote in November 2021 to the leaders at the church I attend — as discussed here in this post:

[ii] Christ takes our suffering — citing Hebrews 2:9 and 1 Peter 3:18:

…we… see Jesus …now crowned with glory and honour because he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.

…Christ… suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, to bring you to God. He was put to death in the body but made alive in the Spirit.

[iii] Christ ends our suffering — citing Henri Blocher writing in Evil and the Cross:

At the cross evil is conquered as evil… evil is conquered as evil because God turns it back upon itself. He makes the supreme crime, the murder of the only righteous person, the very operation that abolished sin… No more complete victor could be imagined… God entraps the deceiver in his own wiles.

He then concludes the chapter with the example (p179) of a sufferer restored in chapter 5 of Mark’s gospel, in the account of the healing of a sick woman that is woven into the narrative of a dead girl being raised to life. I find this an extraordinary episode in Jesus’ ministry, not least because it shows how — in contrast to the normal course of events — the woman is cleansed by contact with Jesus, rather than Jesus being made “unclean” (cf. Leviticus 15:19-30) by contact with the woman.

Chapter 15: Churches that Care Well

In the final chapter, Midgley opens on a realistic and positive note (p183):

Not many of our churches — and not many of us individually — will feel that we have expertise in the care of those who have suffered trauma. The very nature of trauma can leave us feeling overwhelmed. We can’t see what difference our contribution is going to make. Our limited, far from expert input seems so insubstantial in the face of trauma that someone has faced.

Yet we can make a difference. And it’s not necessary to be experts to do so… Any church can demonstrate humility by being willing to listen to those affected by trauma and adapt its care accordingly.

He contends that:

We cannot fix everyone’s problems, and that’s not what we are called to do. We can persist in compassionate care; we can persist in holding out hope and love; we can persist in pointing people to Christ, and we can persist in praying.

And that:

A community that does these things, in reliance on the Spirit, has something very powerful and very significant to offer.

He then follows up two of the examples used in Chapter 3, and shows how church care can work well.

And he ends this relatively short chapter — and the book — with these apt words from 2 Corinthians 1:3-4:

Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God.

I wonder how God views the levels of compassion and comfort in the church today, not least in the context of the experiences of people in the covid era that I noted (here in part 1) could be considered as contenders for “big T” trauma status. I also wonder how those people view the church.

Appendix

Finally, at least in relation to Understanding Trauma, I thought it worth highlighting — and commenting briefly in the context of — some of Midgley’s comments from the Appendix, made (p194) under the heading of The broadening (and trivialising) of trauma:

The wide range of approaches currently available in the field of “trauma therapy” suggests we are still in a period of transition. At present the category of “trauma” functions something like an umbrella term and includes many different experiences. As this field develops, there is like to be a further delineation of separate sub-categories of trauma.

Acute, chronic and complex trauma are already widely recognised categories. Other sub-types are also emerging, such as childhood developmental trauma, collective trauma (something experienced by a large number of people simultaneously), and intergenerational trauma.

I wonder whether the covid era will eventually be recognised as a form of collective trauma, not least in the context of the apparent direct application of Biderman’s Chart of Coercion as discussed in this post:

He continues:

The related concept of moral injury has been used to describe what happens when someone undergoes an experience that is contrary to their moral beliefs.

And gives a couple of scenarios:

Military personnel, for example, would suffer a moral injury if they were forced to follow orders which were contrary to their own moral code.

And:

Other researchers use the concept of moral injury to describe the experience of being caught up in a work environment that a person believes to be morally wrong but where they feel powerless to bring about change. For example, health personnel with an excessive workload might feel unable to deliver the standard of care they consider adequate — this would lead them to feel a moral injury.

To me, this is a missed opportunity to point out what is a strong contender for the most egregious widespread infringement of human rights of modern times, and something which surely exemplifies moral injury. Namely that, during the covid era, health care workers were threatened with losing their jobs — and their livelihoods — if they did not take a novel gene-based injection which plainly had (and still has) no long-term safety data. And in some cases something similar happened if they were merely courageous enough to speak up for their patients on matters relating to basic informed consent.

In the current environment, it seems it is alas necessary also to point out that such principles apply to any medical product that does not have robust long-term safety data. And indeed to any medical product at all.

I am reminded of this post:

That said, I do reiterate what I said at the start of the first in this series of posts, that I thoroughly recommend Understanding Trauma to any Christian interested in showing compassion and care for those who have suffered.

“Societal PTSD”

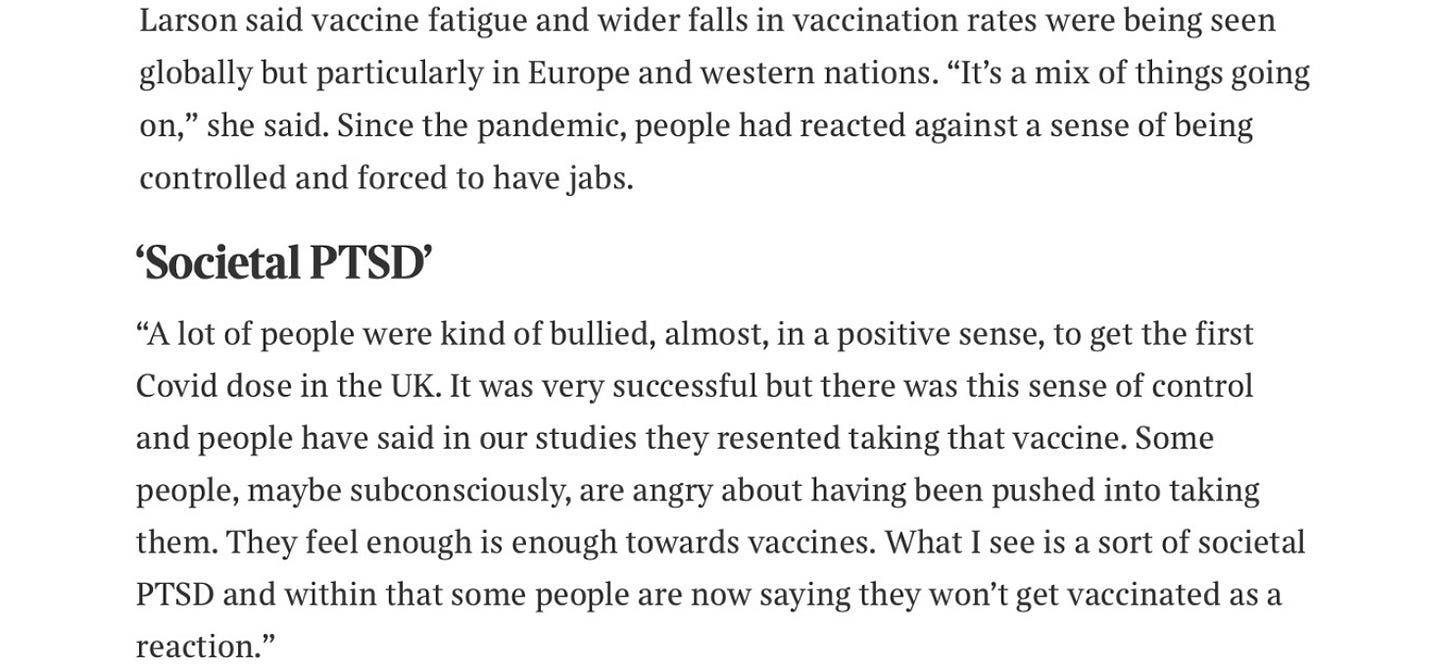

As something of a footnote, in the context of the covid era I wonder to what extent we are now collectively in something resembling the “Avoidance Stage” of what professor of anthropology Heidi Larson calls ‘Societal PTSD’ in this recent Sunday Times article:

“Frontline NHS staff… shunning the flu vaccine… almost nine in ten staff… unvaccinated [in some areas]…”

It sounds like the vast majority of NHS staff could now reasonably be described as “anti-vaxxers”…?

As to the context for the use of the phrase “societal PTSD”, here is a snapshot of the Internet Archive version of the article:

“Bullied, almost, in a positive sense…” is an interesting choice of words. I wonder how much thought Prof Larson has given to informed consent as discussed e.g. in the paper featured in this post:

As to why the vast majority of NHS staff might be refusing flu jabs, Larson cites “toxic information”…

But I wonder how many doctors and nurses would actually say that it was toxic information that was putting them off the flu jab.

And how many would, confidentially at least, cite being coerced, even bullied — and perhaps not “in a positive sense” — into taking the “safe and effective” covid injections.

I suspect that most medics are now at least somewhat aware of what has been going on…

…even though, despite the duty of candour, few of them seem to be willing to say much about it.

It will be interesting to see what happens following the “Avoidance Stage” of ‘Societal PTSD’…

Related:

Dear Church Leaders homepage

Some posts can also be found on Unexpected Turns

Revealing Faith: Seeing and believing the revelation of God (to be published July/August 2025)

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered as the solution to a problem

In some versions, the second of part of that verse is rendered: “think about the things that are… right and pure and beautiful…” (Emphasis added)

Many versions translate the last part of Psalm 31:5 as “God of truth”

![The Chart of Coercion [2025 re-issue]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zk1L!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4cd9bf2a-28c3-4238-a064-802bda8543c9_756x636.png)

![The Day the Dam Broke [2025 re-issue]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UqLH!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbf808d68-6fb1-487c-bc39-6d80a22a9d2a_990x792.png)