Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

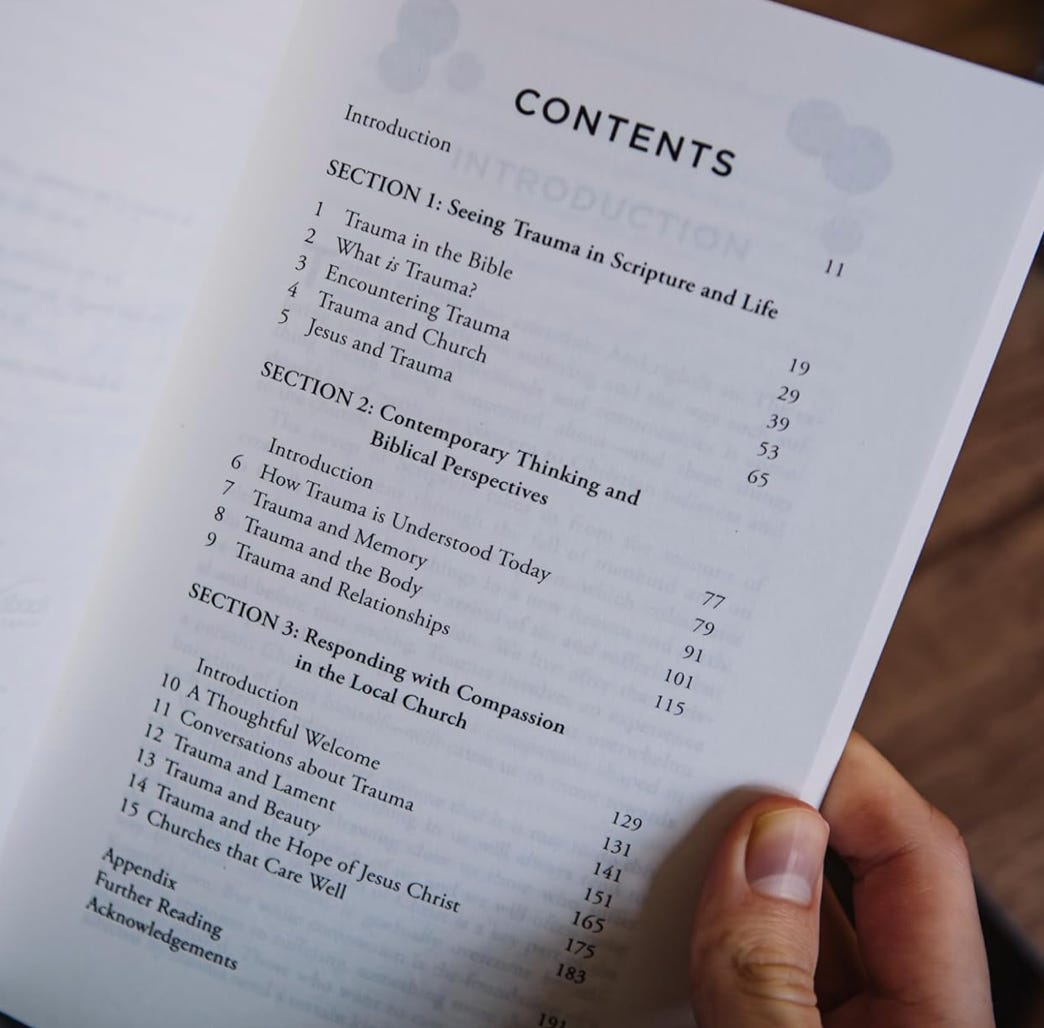

This is the second post in a three-part series on the book Understanding Trauma by Dr Steve Midgley, a qualified psychiatrist who became a pastor and who is now Executive Director of Biblical Counselling UK.

Part 1, subtitled Seeing Trauma in Scripture and Life, provides important context:

Section 2: Contemporary Thinking and Biblical Perspectives

Introduction to Section 2

In the introduction to Section 2, Midgley pushes back on the notion that Bible-believing Christians are well equipped to think about and respond to the experience of trauma. He makes the case that there are many reasons why they find engaging with trauma difficult, not least the fact that (p77):

Trauma disturbs and disrupts, and there is something in us that always wants to retreat from such experiences. We prefer not to have our sense of tranquillity disrupted, and we would rather our sense of safety remained undisturbed.

That seems to me consistent with the fact that many Christians — and particularly church leaders — do not want to engage with what was actually going on during the covid era.

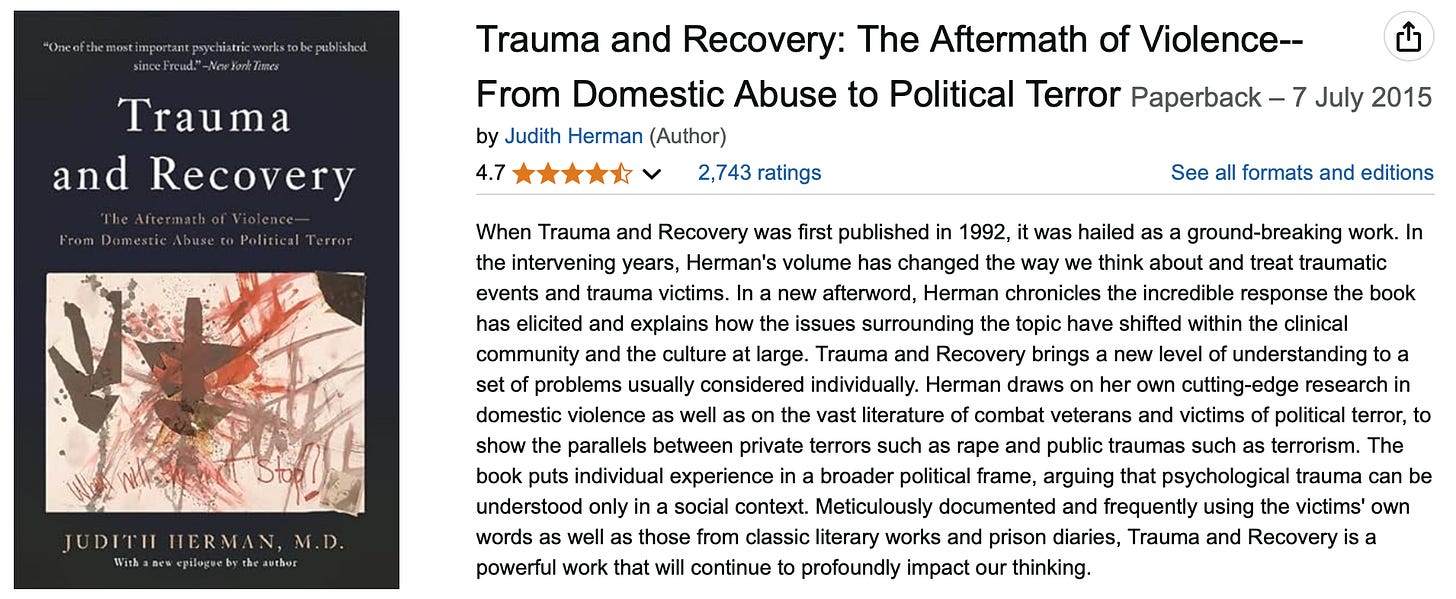

Midgley quotes Judith Herman’s 1992 book Trauma and Recovery to emphasise his point:

To study psychological trauma is to come face to face both with human vulnerability in the natural world and the capacity for evil in human nature…

The past few years have left me wondering whether church leaders actually believe what the Bible says — and what they preach — about sin.

Midgley also notes that the language used in trauma studies is unfamiliar to many church communities. And he says he is seeking to:

“normalise the abnormal” by trying to show how concepts that may feel abnormal and strange to many of us are connected to experiences with which we are already familiar.

Chapter 6: How Trauma is Understood Today

Midgley begins Chapter 6 with another quotation from Judith Herman (p79):

The ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from consciousness. Certain violations… are too terrible to utter aloud: this is the meaning of the word unspeakable.

This too can, I think, be applied to aspects of the covid era. I am reminded of e.g. this post:

As Midgley notes (p80):

For many who are caught up directly in trauma, the experience is so overwhelming that words really do fail them.

He goes on to quote Herman again, who says that, given the choice, we often prefer to believe the perpetrator rather than the victim:

All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing.

Midgley comments that:

We wish to face no disturbance to the calm perception of the world that we have previously constructed.

And adds (from Herman):

A veil of oblivion is drawn over everything painful and unpleasant.

He observes that:

Perpetrators play upon this tendency; they rely on the desire to overlook and rest that which is uncomfortable, unpleasant and disturbing.

And adds (from Herman):

Secrecy and silence are the perpetrator’s first line of defence. If secrecy fails, the perpetrator attacks the credibility of his victim.

I am reminded of the phenomenon of the bystander effect and Stockholm syndrome discussed here in this post:

Midgley points out that:

The victim, by contrast, cannot forget. They may well want to forget but, as we will see, the memory of what happened refuses to be quiet…

And adds that:

Understanding these elements in the dynamic of speaking about and hearing about trauma is vital, for unless we see and understand the way these powerful dynamics operate in our churches, they will be at work without us realising it and will render us liable to ignore those who have suffered trauma.

Still worse, they may cause us to silence those who are trying to find the courage to speak (Emphasis added)

“They may cause us to silence those who are trying to find the courage to speak…” I cannot help but recall the first article I posted on this Substack, featuring a letter to the leaders at the church I attend.

I don’t recall receiving a reply.

Midgley goes on (p81) to give an illustrative general list of contexts in which trauma may be experienced, and applies some of them to the context of church. He then discusses some immediate responses to threat — starting with the relatively well-known fight, flight and freeze, and also discussing fawn (a submissive response), flop (an extreme form of freeze) and fright (hyper-arousal).

He then goes on to discuss (p84ff) the label PTSD — post-traumatic stress disorder — that is often used to describe a cluster of symptoms that are frequently seen in the aftermath of trauma. The features of PTSD are described under three broad headings that are often used:

Hyperarousal — including “shell shock” and feeling “jumpy”

Intrusion — including flashbacks as a kind of re-experiencing of the traumatic event

Numbing — including feeling emotionally numb and detached and with a lack of interest in activities previously enjoyed

These themes are further explored in the remaining chapters in Section 2: Trauma and Memory; Trauma and the Body; Trauma and Relationships

Chapter 7: Trauma and Memory

Midgley begins Chapter 7 by noting (p91) that:

Central to understanding the impact of trauma is the way extreme suffering is simply too much for a person to cope with.

And that, in the words of Judith Harman, trauma involves:

…intense fear, helplessness, loss of control and the threat of annihilation.

He adds that:

Such experiences overwhelm someone’s normal capacity to cope. Nothing in their prior experience has prepared them either to comprehend or to navigate what is happening…

A traumatic event bombards a person not just with external stimuli… but also with their own internal sensory experience. Feelings of panic, terror and dread may all be part of their response to what is happening. In normal situations of danger and threat, we are preparing either to defend ourselves or to flee, and our bodily responses mobilise us to respond. One of the key features of trauma, however, is helplessness — a person can neither resist nor escape. This is understood to be central to the physiological and psychological impact of trauma. (Emphasis added)

That sounds like textbook psychology which would, I presume, be familiar to many of those in the UK government’s Behavioural Insights Team featured in this post:

As to “helplessness… a person can neither resist or escape…” and “feelings of panic, terror and dread…” I am reminded of a document produced by the SPI-B — the Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviour (part of the SAGE behavioural team that gave official evidence to UK government) — that stated on 22nd March 2020:

A substantial number of people still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened…

Part of the context for that document is that, according to the UK government’s Office for National Statistics, the number of people dying was at or below normal levels for the time of year, even though covid had reportedly been in circulation since the end of January:

For many, the feeling of personal threat, and indeed sense of helplessness — the inability to either resist nor escape — was substantially enhanced by the lockdowns that were announced on the following day…

Back in Chapter 7 of Understanding Trauma, Midgley notes that the experience of helplessness…

…seems to cause disruption of normally connected responses — memories and emotions get separated…

And quotes Judith Herman again, writing in the early 1990s:

The human system of self-defence becomes overwhelmed and disorganised… Traumatic events may sever these normally integrated functions from one another. The traumatised person may experience intense emotion but without clear memory of the event, or may remember everything in detail but without emotion.

He goes on to discuss memory in the context of trauma, noting (p92) that:

[While] standard memories appear to be recorded in narrative form… a beginning, a middle and an end… the memory of traumatic events seems to be distinctly different… the imprint that arises as a result of trauma seems to consist of something more like isolated fragments…

He says that:

This essentially fragmentary form of traumatic memory is thought to be connected to the experience of flashbacks, when a person does not so much remember an event as relive it…

And goes on to discuss this in the context of sexual abuse at a young age where the victim may have no organised memory of the event.

More generally, he says that:

Even when a traumatic event is not remembered, it can still be evoked [by sights or sounds or smells]

And that:

In the absence of a narrative memory of the event, the response will be as mysterious to others as it usually is to the person themselves.

In terms of supporting someone telling their story, he notes that:

In the broadest terms, supporting someone… is understood to involve three steps… [i] the need to establish a safe and secure setting in which to begin the process of remembering… [ii] the process of recalling… [iii] establishing a new way forward…

Which, as he acknowledges, is only a rough outline which hardly begins to capture the complexity of the process.

He then goes on to give an example of a man whose child had experienced a life-threatening medical emergency, and makes this observation:

One of the difficulties in his experience of trauma was that he and his wife had responded in very different ways… These differences and his own inability to talk about what had happened with anyone, including his wife, had led to an increasing disruption in their marriage.

I am reminded of the very different ways in which people responded to the events of the covid era, and the apparent inability of some — even now — to talk about what happened. To say nothing of the effect on relationships…

The short story featured in this post also springs to mind:

In the remainder of the chapter, Midgley discusses Old Testament narratives which record suffering and struggle, noting that, while the historical books provide detailed narrative accounts, some of the psalms — 78, 105, 106, and 135 and 136 — provide important additional material. And he considers the notion that revisiting the horrors of the past may actually be beneficial.

I wonder if he would extend that to the horrors of the recent past, not least the examples from the covid era cited in part 1…

Chapter 8: Trauma and the Body

Midgley begins the next chapter by pointing out that:

…[while] our understanding of the complexity of the human brain has only increased in recent years… the range and specificity of the drugs available to us have not altered fundamentally.

And yet:

…a biological approach to mental health problems still predominates… [something] which reflects the current tendency to pay more attention to the material than to the immaterial. Body, rather than soul, has our attention.

I am reminded that, for a substantial number of people, not least the young, the side-effects of mental health drugs are catastrophic and life-changing:

Midgley goes on to provide a brief summary of theoretical approaches to trauma that emphasise its biological basis, while acknowledging that (p101):

…articulating a theory for the biological basis of trauma can never provide a comprehensive understanding of what happens when a person is impacted by trauma. We are more than our biology and we are more than our brains…

I found his approach on this topic refreshing, not least his comment that (p102):

The history of science makes clear that scientific theories must always be considered to be provisional.

In contrast to the notion that “the science is settled”…

That said, he acknowledges that (p103):

This does not mean that the theories which describe the impact of trauma on the basis of changes in the anatomy of the brain should be dismissed or ignored.

And he goes on to describe “A neuroscientific theory of trauma” (p105ff):

…an (inevitably simplified) account of the trauma theories that our culture increasingly uses to describe and understand the experience of trauma…

The triune brain theory — describing the human brain as having three distinct elements: the “reptilian brain”, the “mammalian brain” and the neocortex or “new brain”

Brain functioning in response to danger

Altered brain function following trauma — including the notion of the “switching off” of the rational brain in favour of “emotional brain”

Brain functioning and memory

He outlines some positives in relation to the above, and also some concerns, not least that connecting the impact of trauma with changes in brain structures (and all the attendant complexity) can feel disempowering, which can result in an undesirable “hands off, steer clear” attitude.

He notes that the field of neuroscience is not of one mind on such theories, and quotes Lisa Feldman Barrett, a leading neuroscientist who says, in her book Seven and a Half Lessons about the Brain:

The triune brain idea is one of the most successful and widespread errors in all of science. It’s certainly a compelling story, and at times, it captures how we feel in daily life… But human brains don’t work that way. Bad behavior doesn’t come from ancient and unbridled beasts. Good behaviour is not the result of rationality. And rationality and emotion are not at war… they do not even live in separate parts of the brain.

He concludes:

Some measure of scepticism, without abandoning an interest in theoretical ideas, is warranted. We would do well to approach trauma with an interest in what is observable. We should also do so without losing confidence in the idea that wise and thoughtful care from the people of God remains relevant and important.

Chapter 9: Trauma and Relationships

Midgley begins the final chapter in Section 2 by noting perceptively (p115) that:

There is something in our conversations about trauma that seems to push us towards a very individualistic perspective. We identify a traumatised person. He faced a terrible experience of suffering, and it affected him. She is now someone suffering with post-traumatic stress. Yet this tendency to think and speak in such individualistic terms risks contributing to one particularly troubling impact of trauma — that of feeling profoundly alone.

Helplessness is an invariable element in the experience of trauma. A person not only feels unable to help themselves but also isolated from outside help. No one comes close… the absence of speech produces barriers that prevent others from even being told of the awfulness of what has taken place. Without being able to convey their experience of harm, they are alone with their suffering.

In the context of recent years, the second part reminds me of the testimony of people injured by the covid injections, such as the two featured in these posts:

Midgley notes (p116) that:

Those involved in trauma research describe the key role played by the community that exists around a person impacted by trauma.

And adds:

It is not difficult to see the implications for the role a local church can play in trauma recovery. The qualities that God intends to be embodied within the community of the church are uniquely suited to the care and restoration of those affected by trauma.

At least in theory.

In a section entitled The relational impact of trauma, he notes (p116) that:

Helplessness adds to the sense of isolation. There was no one to call for help. Or perhaps there were people to call to, but a response was not forthcoming. People did not seem able, or willing, to hear the cries for help.

And perhaps to listen carefully to what the person had to say.

In the next section, entitled Making things worse, he observes (p118) that, in general (emphasis added):

The sense of isolation and shame felt by someone who has experienced trauma is intensified when their community proves uncomprehending. That community could be society at large or a more specific community, such as church or family. Sometimes a community is unwilling to listen to those who have experienced trauma. What has happened may seem too difficult or too complicated or too disturbing. Listening may require a shift of perspective that the community is determined to resist, or it may require some specific action that the community is unwilling to perform.

This may lead a community to minimise or even directly refute the account told to them. Minimisation and denial are more likely if the account of trauma has implications for those in positions of authority and power…

In the context of implications for those in positions of authority and power, I cannot help but recall the well-documented accounts of child sexual exploitation in the UK, and the ways in which the victims of such abuse have been treated, including by the BBC as discussed towards the end of this section of this post:

As to listening requiring a shift of perspective that the community is determined to resist, or some specific action that the community is unwilling to perform, I am reminded of the response of the leadership at the church I attend, as I have tried, one way or another, to alert them to the deception of the past few years:

In that context, “determined to resist” seems a particularly apt phrase, at the time of writing at least. And in terms of specific actions that the community (or at least its leadership) is unwilling to perform, I would point to the refusal even to sit down for a normal conversation with concerned members of the congregation.

Midgley goes on to add:

When a victim has found the courage to speak and is still not heard or believed, they feel even more isolated and alone. Suggestions that they are exaggerating what has happened, or at the very least are being oversensitive, only add to their sense of shame.

These responses reinforce the sense that the world is not safe. People are not proving trustworthy or reliable. The cry for help is not heard, and no one comes to offer aid. Feeling of helplessness and lost trust are intensified.

When a church fails to respond to someone who has experienced trauma or where it responds by minimising or even deriding someone’s experience, those attitudes can come to be associated with God. If his people don’t want to hear, perhaps God doesn’t want to either. If his people won’t help, presumably nor will God…

In the next section, Bringing support and healing, Midgley helpfully points out (p119) that:

Responses that offer support and healing are the inverse of those just outlined. This involves a community listening to accounts of suffering and seeking to fully understand them. It means a community acknowledging the wrong that has been done, even if (in fact, especially where) the community itself is implicated in the wrongdoing.

And that:

When a community acknowledges the things that have happened, the sense of isolation changes… Of course, tacit acknowledgement will not suffice. It takes time to truly understand what has happened and the way that it has impacted the person concerned. A community needs to give sufficient time to listening.

He concludes the chapter with a section entitled Gospel-shaped relationships in the context of trauma, which discusses (p121) how:

…there are some aspects of a Christian community that are uniquely relevant to the care of person who has suffered from trauma.

He identifies three broad gospel themes and shows how they are connected to the care of individuals who have experienced the impact of trauma:

Identity — which is rooted in the grace of God, and is given not earned (Ephesians 2:8-9)

Acceptance — which is rooted in belonging to the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:12-26)

Involvement — which is rooted in works of service (Ephesians 4:11-13)

As I see it, those three points are good and important aspects of the care of anyone who has experienced the impact of trauma. But I think that if I were asked to identify gospel themes in that context, I would nominate truth — including an open acknowledgement of the reality of what has happened. And also, particularly where other members of the church community are involved, reconciliation — which is surely among the most important aspects of the gospel (cf. 2 Corinthians 5:11-21).

Part 3 can be found here:

Related:

Dear Church Leaders homepage

Some posts can also be found on Unexpected Turns

Revealing Faith: Seeing and believing the revelation of God (to be published July/August 2025)

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered as the solution to a problem

![The Day the Dam Broke [2025 re-issue]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UqLH!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbf808d68-6fb1-487c-bc39-6d80a22a9d2a_990x792.png)

![An appalling and horrible thing has happened in the land: the prophets prophesy falsely [and] my people love to have it so...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GVTV!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3053f6a6-3b0e-49a7-9e3e-49d31939a022_808x652.png)