Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

For various reasons, I read the recently published book Understanding Trauma — A Biblical Introduction for Church Care — with interest:

One reason is that I had the privilege of hearing the author — Dr Steve Midgley — preach regularly some years ago. He had worked as worked as a psychiatrist in the NHS before becoming a pastor. And he is now the Executive Director of Biblical Counselling UK whose vision is for all people, whatever their struggle, to find wise, biblical conversational ministry in their local church. BCUK offers a range of training courses:

But another reason for reading Understanding Trauma is the context of what I have come to view as something resembling a form of collective trauma that was visited upon the world’s population at large during the covid era under the guise of “a public health emergency”.

The deployment of behavioural psychology…

…has been so successful that few people have begun to recognise the psychological abuse…

…to which we were subjected in the name of “safety” and the “welfare of the people” which has always been the alibi of tyrants:

I was particularly struck by how closely the events of the covid era resembled the textbook psychology that is Biderman’s Chart of Coercion:

The use of the word “trauma” in the context of the covid era

At the outset, I should make it clear that I found Understanding Trauma well worth the time, and would very much recommend it, particularly to those with an interest in how churches can walk with wisdom and compassion alongside those who are struggling with trauma.

But before discussing the book’s contents in more detail, I thought it worth noting that, although the book was published this year, there is only a passing mention of the covid era, in the context of the use of the word “trauma” (p31):

Because the word “trauma” is used in [lots of] different ways, misunderstandings are inevitable. When someone talks about trauma, they may be doing so in a colloquial and casual way or with a formal medical diagnosis in mind. It’s somewhat similar to our use of the word “depression”, which can also be used in a very wide range of different ways.

The Covid pandemic only increased references to trauma. Lockdown experiences were identified as a society-wide trauma that affected all of us. It was an opinion piece about our experience of lockdown that spoke of “how trauma became the word of the decade”.

The problem with the language of trauma becoming more and more widely used is that it begins to lose its meaning altogether. If everything negative is trauma, then in one sense it becomes a meaningless term. The focus of this book will be on “big T” trauma — on the rare and more exceptional events (whether one-off or repeated) that result in people experiencing ongoing struggles in daily life.

I think the general point about language is a fair one.

But I am reminded of what I suspect many people — even some psychiatric professionals — would view as genuinely traumatic experiences of the covid era, at least some of which I think could be considered as contenders for “big T” trauma status.

Examples of experiences of the covid era that could be considered as contenders for “big T” trauma status

The experience of children as described in e.g. the “Abuse and neglect” section of this post…

Some incidences of “abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic” were eventually recorded for posterity here:

The stories of many more children remain untold.

The experience of children such as 15-year-old Canadian schoolgirl Liv McNeil, whose three-minute film Numb made in 2020 is featured here in this article:

A whole generation of schoolchildren have yet to tell their stories.

The experience of the likes of Rosie Tilli, a young Australian, who suffered devastating and life-changing side-effects of SSRI antidepressants she was prescribed in the context of not being able to cope with the isolation of covid lockdowns:

The harrowing experiences in the UK of some pregnant women, their partners and their newborn babies due to “covid restrictions”:

The experience of people such as children’s author Michael Rosen, who was, like many others during the covid era, denied antibiotics for the treatment of pneumonia, and nearly died as a result:

These recent testimonies at the Scottish People’s Covid Inquiry in relation to the experiences of people in care homes and their relatives:

The experience of those who, in the context of having been confined to their homes for months on end, felt pressured…1

…including by church leaders…

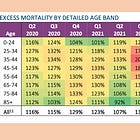

…into taking novel-technology so-called vaccines with no long-term safety data, which appear to have made a very substantial contribution to the additional 2% of the UK working age population — around 800,000 people — being unable to work because of long-term sickness:

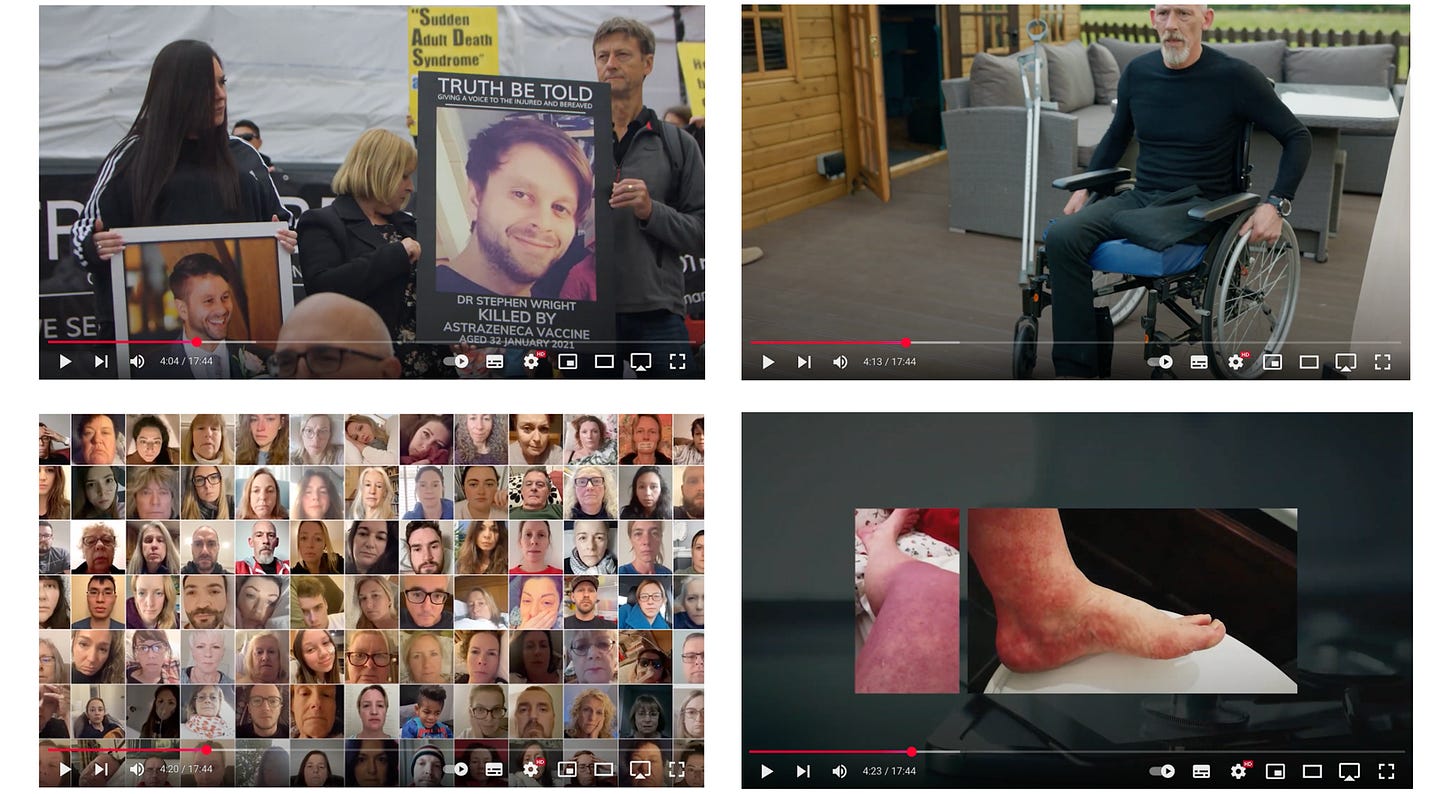

I am reminded of the video featured in this post…

…and the personal stories of the likes of Alex Mitchell (below, top right), who lost a leg, and very nearly his life, as a result of taking an injection he was told was “safe and effective”:2

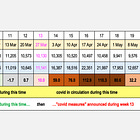

All “for your safety” — from a virus that had reportedly been circulating for two months before lockdown was announced, and yet had resulted in a death rate that was, according to the UK government’s Office for National Statistics, at or below normal levels for the time of year:

Understanding Trauma: Introduction

But that aside, there is a wealth of useful material and timeless wisdom in Understanding Trauma.

The book consists of three main sections, each featuring several chapters:

And each chapter ends with questions for reflection:

The 6-page Introduction is free to read here, and it is well worth looking through it — or the somewhat abridged version below — to set the scene for the rest of this article and the two that will follow it:

Trauma captures our attention. And rightly so. The experiences of extreme suffering and the way such suffering can impact individuals and communities is something worth being concerned about — and these things should be of particular concern to Christian believers and to the church…

Christian compassion — a compassion shaped in imitation of Jesus himself — will cause us to move towards such suffering and pain.

We should not, however, assume that it is easy to do this either wisely or well… while compassion is the foundation of a Christian response to suffering, something more than compassion is needed. Those who want to care well for people affected by trauma need a certain kind of knowledge as well...

In writing this book, I have had four central aims.

1. To engage in an area of important pastoral concern.

2. To summarise secular insights on the experience of trauma.

3. To provide a biblical perspective on trauma.

4. To provide practical pointers toward the care churches can offer to those who have experienced trauma.

…there will always be a point where wise pastoral carers will know that they have reached the boundaries of their competence. At this point, wisdom dictates that the loving thing to do is to recruit others with more expertise and experience. But before that point is reached, churches can, and should, aim to make a real difference. Even when others with more expertise are involved, churches will still want to do all they can to provide a supportive and loving community.

It is also wise at the outset to identify some of the things that this book is not.

First, it is likely that, in places, this book will not be an easy read for people whose own experience has involved severe suffering…

Second, this is not a counselling manual. It will not equip anyone to provide technical or specialist care…

Third, therefore, this is not a comprehensive survey of contemporary thinking in the field of trauma studies... That field is too large and is developing too rapidly for this short volume to be anything other than the very briefest of introductions.

Fourth, in writing this book, it is Christian believers that I have had in mind… this inevitably means that I have made certain presumptions about prior thinking and understanding.

For some, what follows will be frustratingly simplistic. They will notice all sorts of detail that is lacking and which they consider vital. Others, by contrast, will find the material unnecessarily complex and be frustrated by how long it takes to arrive at what they see as the simple truths of the gospel. I have been well aware of both possibilities — you can judge the extent to which I have successfully navigated between them…

In the remainder of this post I will discuss Section 1: Seeing Trauma in Scripture and Life with references here and there to the context of the covid era. I will consider the second and third sections similarly in two subsequent articles.

Section 1: Seeing Trauma in Scripture and Life

Chapter 1: Trauma in the Bible

Midgley begins the opening chapter — of which there is a snapshot (above) in the information on various websites — with a contemporary re-telling of a Bible story (p19). He then provides a brief survey of Scripture that shows (p26):

…that the Bible never shies away from suffering and struggle.

I was particularly struck by a point made (p23) about the:

…misuse of power in the actions, or more accurately the inactions…

…of one very prominent Old Testament king. Although he is furious at the trauma he sees inflicted, his emotion is not followed by action. While he has…

…the power to bring justice, the power to condemn the guilty and the power to bring solace and care to the victim… he does none of these things.

It was a reminder to me that, while everyone has a role to play in the context of helping those who have suffered trauma, some people have a much greater voice and influence than others.

And that, aside from the epilogue, these are the final words of the Bible’s book of Proverbs:

Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.

Midgley ends the chapter by highlighting Jesus’ death on a Roman cross which he says:

…offers an ultimate transformation that can speak to any and every trauma.

He notes that:

…as we try to bring a biblical perspective to contemporary experiences of trauma, we will find that we are well equipped. Scripture speaks to these experiences. The gospel has words of comfort and hope more powerful than any words we might muster up. We have something to say.

But with this important caveat:

Yet in order to speak, we must first listen. Faithful comfort and loving hope are always best communicated by those who have taken time to fully understand the sufferings of another.

Chapter 2: What is Trauma?

In Chapter 2, Midgley discusses what trauma actually is, and highlights “the trauma Bible” The Body Keeps the Score (p30), which, as he points out:

…has spent more than 245 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list, 35 of those at number 1, meaning the the concept of trauma is now very much part of the modern Western mindset.

He explains that:

Defining trauma is difficult.

The word is derived from the Latin “to wound”. But the wounding being described when people talk about trauma varies widely…

I am reminded of my earlier comments about the use of the word “trauma” in the context of the covid era.

Midgley notes that:

There is no universally agreed definition of trauma

But cites several common definitions in which:

…two elements are prominent. The first is a distressing event outside the range of usual human experience (though quite what we should consider normal and what we should consider unusual then becomes the question). Often this event involves an encounter with death — a person may experience a direct threat of death themselves or it may involve the death of someone else, which they may or may not have directly witnessed.

The second element is an experience of helplessness or powerlessness…

While reading those words — a distressing event outside the range of usual human experience… an encounter with death… the death of someone else, which… may or may not have been directly witnessed… an experience of helplessness or powerlessness — images such as these sprang to mind:

Midgley then cites one much-quoted definition of trauma:

An event or circumstance resulting in physical harm, emotional harm and/or life-threatening harm. The event or circumstance has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s mental, physical and emotional health, as well as on social and/or spiritual well-being.

Which captures what have been called the “Three E’s”:

There is an event (or series of events)…

…in which a person experiences themselves as powerless as they face something they can neither cope with nor process and…

…which then produces an ongoing effect on that person’s functioning.

Maybe someone will one day write a book on the Three E’s in the context of the covid era…?

I also found these words (p36) particularly striking:

The spiritual and psychological impact of trauma can be expressed in many different ways. Relationships are commonly affected. Trust may have been undermined. Confidence may have been eroded…

While those words are written in a general context, but I was nevertheless struck by their applicability to the covid era.

Before 2020, I would have expected churches to be leading the way in seeking to bring truth and reconciliation in any context where relationships had been affected. But it seems to me that, in the context of the covid era, the leaders at the church I attend (unlike at least a few in the congregation) show little interest in either.

As to the undermining of trust and the erosion of confidence, I cannot help but think about trust and confidence in the medical profession — and not least those who parroted the “safe and effective” narrative for a novel-technology product with no long-term safety data, and who now seem not to want to talk about it despite their duty of candour. I wonder how the levels of trust and confidence will change with the growing awareness of what has actually been going on.

I was also interested to read (p36) that:

Thinking more specifically about Christian believers who experience trauma, some more obvious kinds of spiritual struggle would include finding it almost impossible to pray and equally impossible to meet with other believers, especially in the context of a main church gathering. A person’s relationship with the Lord might well be disturbed as new doubts arise.

Midgley goes on to give multiple examples later in the book.

For the record, I would say that my relationship with God is — by his grace — much as it was prior to 2020.

The remainder of Chapter 2 features a discussion on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is a psychiatric diagnosis given to a person when a series of specific features are present. In closing, Midgley notes:

It is crucial to understand that the experience of extreme suffering can overwhelm someone. The inability to process what has happened in that suffering can impact them in a wide range of different ways and may have profound and long-lasting effects in their life.

A basic awareness of the way people can be affected by trauma will help us to avoid overlooking such struggles in those around us, or failing to consider that behaviour which seems strange or awkward to us may be due to the impact of trauma. A church that is unfamiliar with the way severe suffering can affect a person will fail to care well for such people in their congregation and community.

Chapter 3: Encountering Trauma

In Chapter 3, Midgley begins (p39) by pointing out that:

Since trauma will sometimes be a significant factor in pastoral care, it is important to be alert to it. Yet trauma is often hidden — in fact, at times it may even be hidden from the person themselves. When we fail to see the way an experience of trauma is contributing to a pastoral situation, we risk significant pastoral missteps.

I suppose there are multiple different ways in which trauma may be hidden from a person. I am reminded of people whose health has deteriorated as a result of covid injections but who have not yet made the connection. And as to pastoral missteps, I wonder how much sympathy those who know they are covid vaccine-injured have received from church leaders — or those charged with pastoral care. Particularly when the latter have put their faith in the “safe and effective” narrative, and still believe those who say that such harms are “rare”.

Midgley goes on to give a series of specific examples to illustrate his general point:

Each illustration beings with a pastoral encounter that was puzzling or problematic. What follows is the backstory which helps explain why that initial pastoral contact happened in the way it did.

None of the stories describe real individuals but are composite stories reflecting the experiences of many different people that I have known.

I found these examples poignant and thought-provoking. I wonder how much unspoken trauma there has been in the lives of those I have lived and worked with. And in the lives of those in Bible study groups I have attended and led. And in the lives of those in public life. It struck me that, in our busy lives, allowing people the time and space to talk about what has happened to them in the past is often a low priority.

Midgley concludes the chapter by noting:

Trauma comes to us in so many different forms and is so often hidden from view. Those around us in church may have stories of trauma about which we know nothing. Sometimes those stories will burst into the present in dramatic and disturbing ways…

Those words reminded me of my experience of 5th December 2021, described in A dark day…

…which hardly anyone at church has even mentioned since.

I find it somewhat ironic that earlier in 2021 I had been approached to join the pastoral team at our church. For various reasons, not least the context of what I wrote in January 2021…

…I thought it best to decline.

Midgley continues:

…more often [those stories] will lurk in the background. But all the time, relationships are strained or impaired; daily functioning is disrupted; faith is challenged.

And notes that:

If we are going to support people who are carrying trauma, the most basic requirement is that we are alert to the category in the first place. Unless we consider that trauma is a possibility, we will invariably miss it. And if we miss it, we will never be able to speak the comfort of Christ into its midst.

He then introduces chapter 4 by observing:

But thoughts about how we might be able to offer help are still a long way off. First, we need to recognise how church, instead of offering comfort for trauma, can sometimes contribute to it.

Chapter 4: Trauma and Church

Midgley opens the next chapter (p53) by observing that:

If we are going to commend Christ well in contemporary culture, we need to understand the issues that our contemporary culture considers important. And that includes trauma.

I find that to be a refreshing change from the mantra “I just need to preach the gospel” — described in this post as a “reflection of the collapse of the biblical world and life view within the church”:

He goes on to add that:

Engaging well with trauma, though, involves much more than simply improving our communication. Understanding the way trauma impacts individuals should also inform the way we organise our ministry and our activities…

And then considers harm that can arise in a church context from ignorance, thoughtlessness and abuse.

He acknowledges (p59) that:

We need not think that every church must have in their midst experts in trauma studies and trauma recovery.

But contends that:

What we should ask of ourselves is that we have the kind of understanding that will help our church communities to respond more wisely when we face pastoral issues associated with trauma.

To that end, he outlines three things that will contribute to this:

Firstly, a basic familiarity with the language and terms which are used in relation to trauma… Second, an awareness of the physiological mechanisms that are being identified as underpinning the experience of trauma… Third, all those who care would benefit from having a broad outline of the main types of support that people affected by trauma are usually offered.

He identifies (p60) three broad groups of people who may be represented in any given local church:

… [i] some who work in the caring professions and engage with trauma in their day-to-day work, or whose secular training has prompted a particular interest in trauma studies… [ii] those who are broadly aware of the topic of trauma but who lack any detailed knowledge… [and] [iii] those who take a sceptical and dismissive attitude toward trauma [perhaps] because of a resistance to any perspectives arising from “the world’s thinking”.

He recognises (p61) that:

Most churches will not feel they have the resources or the personnel available which allows them to offer skilled support to those who have suffered trauma…

But says (p62) that:

Signposting people to suitable care, and then supporting them as they receive that care, is a minimum target.

Adding:

It will also be helpful if churches provide a biblical framework that can sit alongside the secular care people are likely to be receiving. Knowing how to think biblically about suffering — including even extreme suffering — is an essential requirement…

And that:

We might also helpfully recognise the differences between complex trauma (which arises from traumatic events experienced over a long period of time and especially in childhood) and single-event trauma…

He also points out, citing Psalm 100:5 among other verses, that:

One aspect of care that church can and should always seek to excel in is perseverance…

And adds that:

It is not unusual to find that as a person begins to address trauma from the past, things get worse before they begin to get better. To imitate God’s love will mean continuing to serve people even when we receive little or nothing in return.

He ends the chapter (p63) by noting that:

Walking alongside those who have experienced trauma is hard. People who offer such support are undertaking a wonderful but also a wearying labour of love…

And:

We must all be alert to the need to care for the carers so that their care can be sustained over the long term, which is so important in relation to recovery from trauma…

But also that:

If you are the one who is walking alongside, you need to give yourself permission to find it hard, and to allow the wider church to help you.

Chapter 5: Jesus and Trauma

In the final chapter of Section 1, the focus is on Jesus and trauma. As Midgley puts it (p65), the chapter:

…serves as both a backdrop and a preview [to later material]

Luke 8 is cited as:

…one of many chapters in the Gospel accounts where we see Jesus engaging with extreme suffering.

And the experiences of various people featured in the second half of that chapter are considered: the fishermen in v22-25, the man in chains in v26-39, Jairus the synagogue leader in v40ff, and a woman who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years in v43ff.

He continues (p67):

Yet we can say more: Jesus didn’t just see and move towards those burdened by extreme suffering and trauma; he experienced it himself.

And he describes how Jesus experienced extreme trauma in his arrest, trial and execution, which is remarkably understated in the narrative of Luke’s Gospel.

He notes out that crucifixion has been described as:

…the most barbaric form of execution ever inflicted. The physical pain from nailed hands and feet was endured under public gaze and lasted for many hours.

And points out, citing Galatians 3:13 — “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us”, that:

…for all the awfulness of the physical agonies… the Bible reveals a further experience of appalling suffering, for in his death, Jesus suffered hell — the spiritual judgement of his Father.

He emphasises (p68) that:

The Bible presents us with a God who knows the appalling experience of trauma from the inside. He has endured physical, emotional and spiritual agonies that we can only begin to guess at.

But observes:

…there is still more to say. It isn’t simply that Jesus understood trauma, nor even that he personally experienced it… the good news about Jesus goes so much further — for, by going to the cross, Jesus was doing far more than simply entering into our trauma. He was working to transform it.

In the subsequent sections, Midgley describes how Jesus transforms our trauma now, giving examples, and how he will transform our trauma beyond this life, when God “will wipe ever tear from [the] eyes [of his people]” (Revelation 21:4).

He recognises that:

None of this is intended to minimise the pain of the present or the profound impact of trauma into the future… The Bible never pretends that suffering is not real, nor that living in this world is easy.

But emphasises that:

…this gospel hope is a real hope, and the comfort that it brings is real comfort…

He closes the chapter — and the first section — by saying (p73) that:

Caring for someone who is carrying trauma, then, must be centred on Christ. That means, first, that we need to depend on Christ for ourselves… second, that we need to aim to be Christ-like in our care… third… we will always seek to direct people away from ourselves and towards Jesus.

On that final point, I am reminded of the words of John the Baptist in John 3:30:

He must become greater; I must become less.

Part 2 can be found here:

Related:

Dear Church Leaders homepage

Some posts can also be found on Unexpected Turns

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered as the solution to a problem

NB the UK got off relatively lightly, not least thanks to the efforts of the NHS100K discussed in this post:

See e.g. this section of this post…

…for details of some of what was happening in Germany.

I was particularly struck by this recent post from US ragtime pianist/satirical songwriter Kylan deGhetaldi (@foundring1):

My kid was kicked out of school and our own church banned her from the premises because she didn’t get a vaccine they now admit isn’t safe for kids to get. They tried to force poison into my kid…

And then there are the statistics on the sharp rise in deaths from 2021 onwards that almost no-one in the public sphere is talking about:

![The Chart of Coercion [2025 re-issue]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4cd9bf2a-28c3-4238-a064-802bda8543c9_756x636.png)

![[SPCI-4]: "Even the organisations... that were meant to look after the interests of the elderly and the frail, they were useless… No-one spoke up for those without a voice, except their families"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F623c947c-f038-4a0c-a4db-a38a129c3730_1154x1012.png)

![[SPCI-5] "I obtained his medical records... My brother had been placed on a trial... I found that his signature had been forged... that withheld the antibiotics"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe32eb6f5-23d5-4883-a735-7b60a66c6971_1450x1400.png)

![[SPCI-6] "I fear my father was euthanised, and I was told not to use that word at the Scottish Covid Inquiry. They did not like me using that word... They don't like the truth..."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe6cc3dd1-2a4a-4753-90a9-c9d9aa638e5b_720x650.png)

![The Day the Dam Broke [2025 re-issue]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbf808d68-6fb1-487c-bc39-6d80a22a9d2a_990x792.png)