A massive culture shift at Wikipedia

How the online encyclopedia changed from a "decentralised database" of knowledge to a "top-down social activism and advocacy machine"

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

I can still remember when I first encountered Wikipedia in the 2000s, following a recommendation from a work colleague.

It seemed like a great concept — an apparently decentralised, open and transparent source of neutral, crowd-sourced, fact-based information (insofar as that is possible). With no adverts.

I recall reports that the online encyclopaedia was more accurate than the likes of the traditional Encyclopaedia Britannica, where corrections and amendments would have to await until the next print run. There were also accounts of mischievous meddling being corrected in short order by the site’s community of dedicated editors.

But at some stage — I cannot remember quite when — I began to wonder. Wikipedia was a free service, and there was at least the possibility that individuals or organisations willing to contribute financially could potentially buy influence. I had similar misgivings about online newspapers like The Guardian and The Telegraph1 which openly take money from the Gates Foundation.

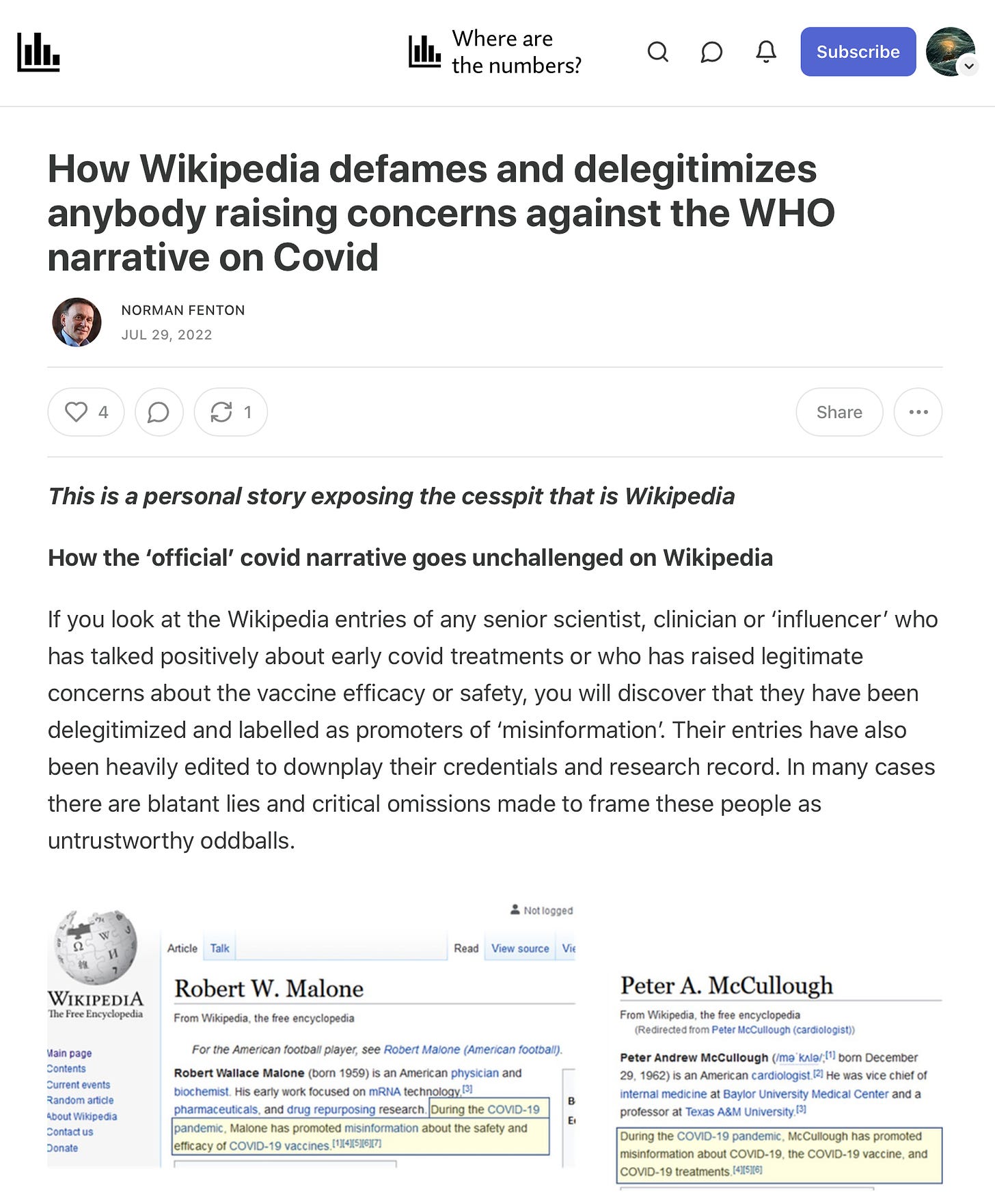

Over the past ten years or so, I have increasingly sensed something of a change. In particular, I noticed how Wikipedia was portraying credible scientists speaking out against the “official” covid narrative, as exemplified by this article from Prof Norman Fenton:

I also saw this interview with co-founder Larry Sanger (starting at 58:08):

Incidentally, when I searched exact wording from the title of that Rumble video, i.e. Wikipedia From Democratized Knowledge to Left-Establishment Propaganda with no quotation marks or colon, the link to the video did not appear on the front page of results on Google. When I searched DuckDuckGo, the results were more relevant, although curiously the link to the video only sometimes appeared prominently. But both Mojeek and Yandex did consistently provide the link on the front page of results. Which is consistent with what I observed here.

As it happens, the role of Google in relation to Wikipedia features in this recent account from Ashley Rindsberg detailing some of what has actually been going on behind the scenes (headings and occasional emphasis added):

TLDR/summary

Wikimedia’s Movement Strategy, which launched in 2017 with a plan to fund Wikimedia “in perpetuity” with its Wikimedia Endowment, was a significant pivot from Wikipedia’s mission: “where Wikipedia had been built on the principle of decentralized knowledge, the Movement Strategy would veer into the hyper-centralized space of top-down social justice activism and advocacy”

The Endowment is an independently governed long-term fund that bankrolls Wikimedia “projects.” It was set up as a donor-advised fund at progressive megafund Tides for its first seven years; Tides’ former General Counsel left to serve as Wikimedia Foundation’s top lawyer around this time

Flush with well over a hundred million dollars in cash, the Wikimedia Endowment has funded initiatives that seek to abolish the police and create an “intersectional scientific method,” among others

A massive culture shift

In 2019, a scandal ripped through the Wikipedia community when a Wikipedia admin who goes by the handle Fram was handed a year-long ban from the site. While known to few outside the tight-knit but feverishly active collective of Wikipedia contributors, the affair was part of a far-reaching, partisan shift at the open encyclopedia with widespread implications for the future of media, technology, and politics around the world.

Although contributor bans are not uncommon on Wikipedia, this case was different. Instead of coming from the English Wikipedia Arbitration Committee (Arbcom), the panel of editors empowered to make such decisions, the ban was handed down directly by Wikimedia Foundation (WMF), the NGO that owns the site.

Little more than 12 hours after the ban’s announcement, Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales publicly intervened to help quell the storm by publicly assuring the community he was reviewing the situation, and later saying he’d “raised the issue with WMF.” A week later, two Wikipedia bureaucrats — high-ranking editors who can assign admin rights — and 18 admins — editors with enhanced rights — resigned in protest. Arbcom released a searing statement saying the top-down ban was “fundamentally misaligned with the Wikimedia movement’s principles of openness, consensus, and self-governance.”

At its lowest resolution, the controversy was born from the tension between the decentralized Wikipedia site and the highly centralized Wikimedia Foundation. In reality, the ban and subsequent backlash were tied to a massive culture shift at Wikipedia, precipitated by the rise of a new social-justice-minded power structure at Wikimedia Foundation.

The launch of Wikiproject Black Lives Matter in 2020 exemplified Wikipedia’s all-in pivot to DEI. Seeking to address what it called Wikipedia’s “systemic bias,” the project called for editors to enrich the content, and elevate the visibility, of pages like “Black Lives Matter,” “Police Brutality in the United States,” “Racism in Oregon” and “US National Anthem Protests.” Most importantly, the project represented a carve-out from Wikipedia’s foundational policy of providing No Original Research: instead of aggregating information from other sources, Wikipedia editors began both going to protests and proactively reaching out to photographers who would be willing to allow Creative Commons use of protest photography.

The controversy was ultimately about who would control the site containing “all the world’s knowledge,” and hundreds of millions in Wikipedia funding. Would the site’s community of decentralized, uncompensated editors continue to govern it according to its principles of openness, transparency, and neutrality, or would a handful of highly paid NGO technocrats re-orient Wikipedia toward endorsing and promoting the ever-shifting currents of the Western elite social justice regime? And how would Wikipedia respond to a revolution in American public life that challenged the idea that knowledge should be both neutral and objective as a vestige of white supremacy?

Rindsberg then describes some of the internal goings-on at Wikipedia, particularly in relation to Fram, and states in summary:

This strange triangle of love, enmity, and power led many in the community to believe that Fram had been banned not for vague accusations of “abuse” but for calling out sub-par work of a top Wikimedia official’s love interest [the top Wikimedia official being Raystorm (real name Maria Sefidari), and the sub-par work being that of editor Laura Hale]

She adds:

Salacious as it all was, if this had been the end of the story, it would have been an unpleasant, but quirky, footnote in Wikipedia history. In reality, it was only the beginning of a fundamental change that would replace the decentralized ethos of the site’s founders, and impose the WMF agenda on Wikipedia to use it as a tool for progressive social change.

And then adds further context:

Two years later, Sefidari [the top Wikimedia official mentioned above] announced that she’d be stepping down from the WMF Board of Trustees. But there was a catch: she would transition into a role as a paid consultant. This immediately set off alarm bells in the community, with members protesting that a senior WMF official taking a separate paid role on exit smacked of self-dealing. The landslide of objections became so intense that WMF’s General Counsel, Amanda Keton, had to step in with a lengthy response.

Keton explained the new arrangement by saying the WMF had identified “gaps in implementation of the Foundation’s Movement Strategy” that required further staffing. Sefidari was supposed to fill this gap, now as a paid consultant, with her extensive knowledge of WMF and the Movement Strategy brought to bear on the work.

The Movement Strategy, also known as Wikimedia 2030, was indeed a massive undertaking. Launched in 2017 by then-WMF executive director and CEO Katherine Maher, the strategy would be a complete re-imagining of WMF and Wikipedia’s mission. Where Wikipedia had been built on the principle of decentralized knowledge, the Movement Strategy would veer into the hyper-centralized space of top-down social justice activism and advocacy. At the initiative’s launch event, Maher told the audience it had taken eight months to fully conceive and would draw in various stakeholders, like media, tech, academics and NGOs. (Among the few directly named was Maria Sefidaris.)

The key concept undergirding the Movement Strategy was “inclusion,” an idea rapidly becoming buzzy amid the swirling culture currents that would soon crystallize into #MeToo, BLM and the trans movement. One of the “Consensus Findings” derived from the process of fleshing out the initiative was a statement that could have come straight from a DEI handbook: “Inclusivity and new representation can be only forged on lower barriers to entry.”

From Maher’s perspective, there was good reason for this newfound focus on inclusion. For all the talk at Wikimedia Foundation about diversity, the overwhelming majority — some 80% — of Wikipedia editors are men. If WMF’s sole purpose was to ensure Wikipedia’s mission of ensuring global access to all knowledge, then, by the logic of the equity-inspired ethos WMF had wholeheartedly endorsed, the organization was unjustly sidelining the viewpoint of half of the world’s population, therefore failing its mission.

As the driving force behind the Movement Strategy, Maher would directly endorse this view in comments revealed after she took the top job at NPR this year, in which she said she opposed the “free and open” ethos of Wikipedia because it was rooted in “white male Westernized construct” that precipitated the “exclusion of communities and languages.”

WMF officially expressed the same view (albeit in more corporate tones) in a 2023 LinkedIn post: “Why does global representation of Wikipedia volunteer editors matter? It matters because Wikipedia is a reflection of the people who contribute to it. Diverse perspectives create higher-quality, more representative, and relevant knowledge for all of us.” This notion, what WMF called “knowledge equity,” would become foundational to the Wikimedia mission.

It was also this notion that drove one of the other Consensus Findings of the Movement Strategy — one strikingly similar in style and substance to ideas advocated by another organization with a three-letter acronym, the World Economic Forum: “Wikimedia should be an influencer in shaping world policy in access to knowledge,” the WMF presentation stated. When the site launched in 2001, this may have been a lofty, even academic, ideal. But in 2017, it was clear that a battle over information would play a critical role in how emergent digital power would get divided up. By that point, content had become the lifeblood of the Internet. It was pumped by its digital heart: Google.

Ah yes, the World Economic Forum. As featured in this recent post:

The role of Google and the Tides Foundation

In this dynamic, Wikipedia played a role vastly more important than any other single website, feeding millions of pages filled with content “verified” by Wikipedia’s army of editors into the search engine. In this sense, the site would serve as a giant outsourced verification service for Google with one exceptionally lucrative benefit — it was free. In return, Wikipedia achieved the equivalent of most favored nation status on the search engine, its pages appearing as the top spot on millions of search results and powering Google’s Knowledge Graph, the panel of information beside search results that, by 2016, appeared in one-third of all Google searches. Google, acknowledging Wikipedia’s importance, contributed throughout the years, starting with a $2 million gift in 2010.

For the [Wikimedia] Foundation’s part, to achieve its goal of “shaping world policy in access to knowledge,” the WMF would need money — lots of it. Accordingly, the Movement Strategy devoted significant focus on funding WMF deep into the future. But it went much further, innovating a new structure for the Foundation that could harness the internet’s insatiable demand for digital information.

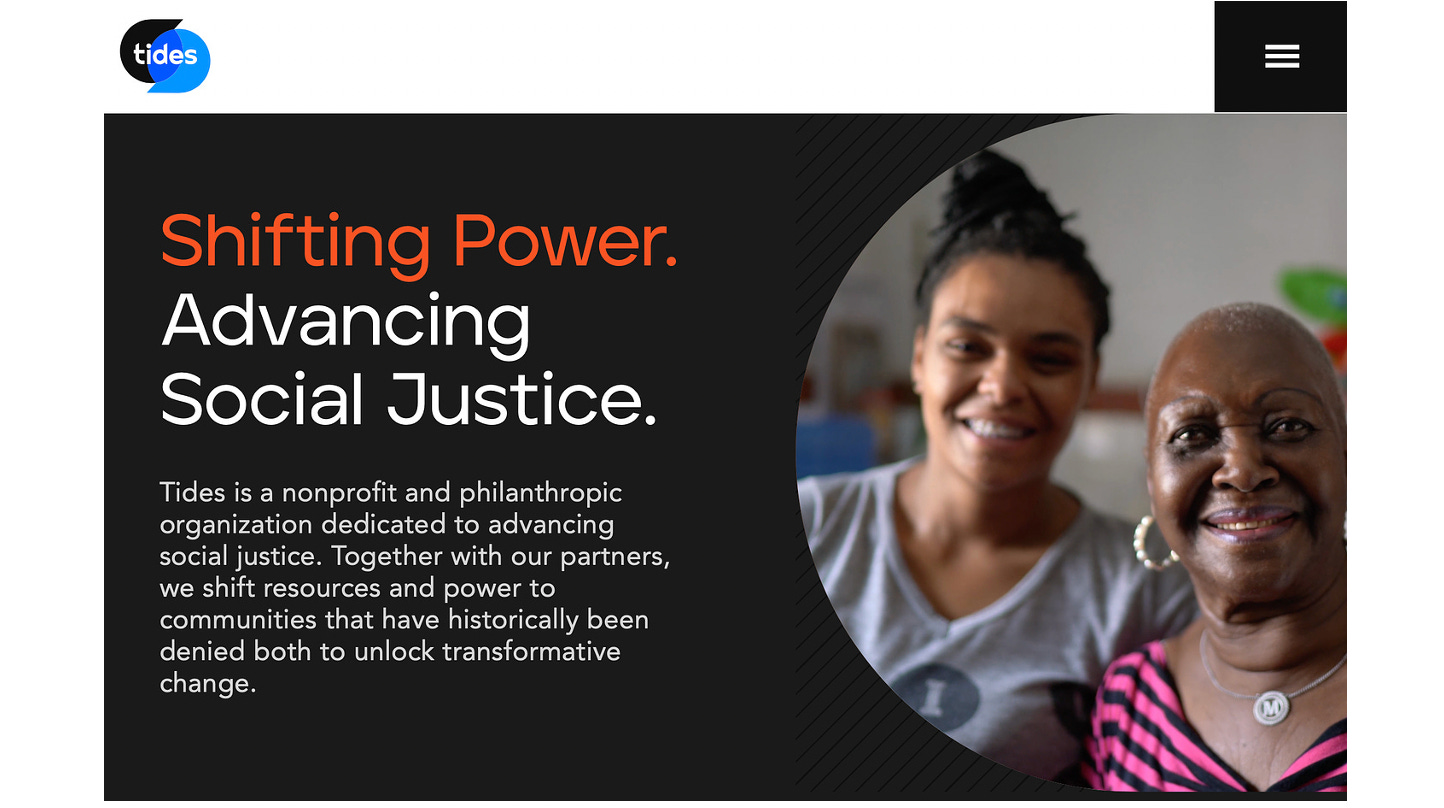

The central aspect of WMF’s new financial strategy was the establishment of the Wikimedia Endowment, a pool of money that, as its name suggests, is designed to fund the organization essentially “in perpetuity.” Distinct from Wikimedia’s budget, which funds Wikipedia’s day-to-day operations, the Endowment was set up in 2016 as a donor-advised fund at leftist mega-fund, Tides Foundation, an $800 million fund that’s part of the wider Tides Center, a network of such funds “that partners with social change leaders and organizations to… accelerate social justice.” The Tides Foundation’s IRS 990 filing lists its mission as “Grantmaking through funds to accelerate the pace of social change.”

Tides, which has received $34 million in taxpayer funding since 2008, funds a variety of hard-left groups focused on defunding police departments, like the Justice Teams Network, which works to defund the Oakland police, as well as Chispa, which worked toward the same end in Santa Clara, California. Tides has also founded numerous anti-Israel groups like the Council on Islamic American Relations, which is an unindicted co-conspirator in a plan to funnel millions of dollars to Hamas. The fund recently made the news for its association with the Arab Resource and Organizing Center, a group it not only funds but operates, which last November led the shutdown of the Bay Bridge to protest the war in Gaza.

Though launch of the Endowment took place under Katherine Maher’s leadership, it would be a Tides executive who would play a leading role in stitching the two organizations together — General Counsel Amanda Keton who, little more than two years later, would move to WMF to serve as its top lawyer (the role in which she stepped in to defend Maria Sefidaris’ paid consultancy). With one of WMF’s most powerful financial engines nested inside of Tides, and a top executive from Tides serving as the head of legal at WMF, the two organizations were all but interwoven.

The stated goal of the Endowment was to raise $100 million in 10 years. By last year, the Endowment had around $119 million in assets in addition to $250 million in assets owned by Wikimedia Foundation. This raises a question: where did this enormous sum come from? One answer lies in Wikipedia’s unofficial content partner, Google. In 2016 — the year the Endowment was established as a part of Tides — Google made its first contribution to the Tides Foundation. The amount, a staggering $59 million, was more than ten times greater than Google’s average donations, which generally ranged from a few hundred thousand dollars to single-digit millions. In 2017, the year the Movement Strategy was launched, Google gave Tides $76 million and followed it up with $45 million in 2018. (The Endowment eventually became a standalone 501(c)(3) in 2022.)

There was good reason for any donor, especially one as high profile as Google, to be incentivized by this new arrangement. As a donor-advised fund, Tides Foundation provides a layer of anonymity to WMF contributors who do not want to be identified. But it also gives known donors a buffer between their contributions and the grants that WMF would make on the other end of the pipeline. Google could donate funds that would eventually get funneled into grants for radical social justice programs with a hefty degree of plausible deniability and no small amount of opacity. Such an arrangement could afford Google, and dozens of donors like it, all the social justice impact with none of the PR-nightmare downsides.

In 2022, Google and WMF went a step further with the creation of Wikimedia Enterprise, a for-profit arm of WMF that would pipe Wikipedia data to enterprise customers, with Google being the first and, at that time at least, only paying customer. Wikimedia Enterprise was launched as a part of the Movement Strategy to, in WMF’s words, achieve the strategy’s two major strategic aims: “advancing knowledge equity and knowledge as a service.”

Flush with dark donations and freshly sourced enterprise cash, WMF leaders did not hold back. A viral X post from 2022 explored some of the more egregious examples, including significant donations from WMF’s Equity Fund, like $250,000 to the SeRCH Foundation, which advocates for creating an “intersectional scientific method,” and another $250,00 for the Borealis Racial Equity in Journalism Fund, which has laid out a plan to raise up to $71 billion for BIPOC journalism while serving as a pass through that funds radical leftwing groups like Assata’s Daughters, a group that seeks to abolish the police.

Donations like these fuel social justice advocacy and activism across the country. But, for the WMF, they’re also just one part of a much larger picture of change. Pursuing its new global vision, WMF is now aggressively lobbying the UN to ensure it can influence the global body’s upcoming Global Digital Compact, a set of guidelines that seeks to regulate the internet the way the UN’s 2000 Global Compact sought, successfully, to regulate world of business through what would become known as ESG and DEI.

There is no doubt that the future is bright for WMF. It is flush with money and has positioned itself at the very center of global governance — the epitome of top-down centralization. But this shining new outlook on controlling who gets to create, spread, own, and even define information is a fundamental philosophical shift from the decentralized vision set out by Wikipedia at its birth as not an entity, but a process for creating knowledge accessible to all — and owned by none.

All of which is consistent with Mathew’s law — coined by Mathew Crawford, the prolific author of the Rounding the Earth Newsletter:

The more political the topic, the less reliable is Wikipedia.

With quite a wide definition of political — as indicated by e.g. Norman Fenton’s article mentioned earlier. I am now wary of any Wikipedia content where substantial vested financial interests are at stake. Which includes anything relating to climate, or wars, or pandemics. Or indeed various other aspects of health.2

Dear Church Leaders articles

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered

In the context of the article’s statement that “this support comes without strings and The Telegraph retains full editorial control over all the content published” I’d be interested to know (for example) why, in contrast to most Telegraph articles, readers were often not allowed to comment on “Global Health Security” articles during 2021-2022