Error hates Truth

The parable of the tape measure, featuring a crucial point about common knowledge

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

In this recent post…

I wrote that:

For me, a strong contender for the best thing about social media is the way that it enables the sharing of information.

And insofar as I spend time on social media, finding useful information is my main goal, not least with a view to exploring “minority reports” as discussed here:

The useful information I am looking for comes in many and various forms: short extracts from books, interview clips, snapshots of government data, details of proposed legislation, long-forgotten wisdom applied to new situations. Etc. Sometimes all the relevant information is in the social media post itself. And sometimes the post is merely a few words along with a link.

Some places are of course much better than others to look for such things.

The parable of the tape measure

I encountered the parable of the tape measure via the X account of Ed Dowd, who featured in these two posts I wrote several months ago:

(If you haven’t read them, I recommend doing so. Both are fairly short.)

Dowd’s social media output is fairly modest, but it has an unusually high signal-to-noise ratio, and little or no footage of felines.1 And in the post in question, which was actually a repost from mathematician James Lindsay,2 Dowd was merely relaying wisdom that apparently originally came from The Honorable Bob McEwan.

But it is of course important to avoid credentialism, and to focus on what is being said rather than who is saying it. And so I have pasted in the post below, and added some comments.

The context here is the sort of situation that occurs when people who are wrong attack people who are telling the truth. And by “wrong” here I mean not just wrong in what is believed, but in what is done in response to that (wrong) belief.

Such attacks can be characterised as Error hating Truth.

Why might Error hate Truth? Consider the parable of the tape measure:

Imagine we’re in an auditorium, and I say the auditorium is 50 feet wide, and you say it’s 60 feet, and someone else says it’s 80 feet. Obviously, we cannot all be correct (although we could all be wrong).

Now suppose we don’t have any way to measure the room but decide it’s important to figure out. I sit there and give my best arguments for 50 feet, and you argue for 60, and the other guy argues for 80, and we appeal to this and that and talk and talk and talk.

It’s all well and good so long as we argue it out, I guess, each gaining support for our case from the audience in the room, which might make us feel good or even give us power to try to call a “consensus” view that shows that we’re right.

Once that power and status element enter the situation, though, all doesn’t stay well or good for long. In fact, our arguments will probably get uglier, and we might motivate our factions against one another. Persuasion might give way to force where it fails to generate consensus

Now suppose someone else walks in the room with the best and worst possible thing: a tape measure. And that person stretches the tape from wall to wall and actually measures the room, finding out the truth of how wide it is. What about that?

Maybe the room is actually 57 feet across, so everyone was wrong. If we’re all just dispassionate fact-finders interested in the width of the room, that’s fine. We’d all humble ourselves, say it was our best guess given the circumstances, and accept the truth.

But if we’ve built power or status, or acted badly, or forced consensus around our view, we aren’t going to like to see that tape measure at all. In fact, we might accuse the person holding the tape of being a problem or of measuring wrong on purpose or any number of things.

We don’t want to be wrong in front of the crowd, especially if our status and reputation are on the line. If we have the power, we might even turn our faction against the person with the tape measure and force them not to measure or to lie about the measurement.

Why? As Bob says, because in the instant that measurement is taken, everyone in the room suddenly knows we’re wrong. Each of us being wrong becomes *common knowledge* in the room, and we’re humiliated to the degree we hung our hat on our belief.

Truth can only be sought in humility and dispassionately, and truth ALWAYS humbles the haughty and lays low the mighty. Nothing cuts across illegitimate or arbitrary power like the truth, and the truth is completely ruthless in cutting across our pride and arrogance.

Truth is also available to anyone who is willing to do the work to seek it; in this case by getting a tape measure and measuring the room. Thus, truth equalizes against all assertions of power, and its power is supreme even without ever asserting itself. It just IS.

Once the truth is out there, there’s no putting it back without making the situation worse for Error. Why? Because everyone who knows the truth and knows it’s known will see the coverup, which discredits Error further, no matter how much force is applied in maintenance of Error.

This raises many important points, but all but one is obvious enough to leave to you, Dear Reader. I’m sure you get them all, though many are deep to the deepest levels and should put you in a holy state of thought about who and what we are and what we have before us.

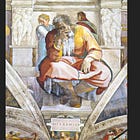

Error hating Truth reminds me of the experience of Jeremiah, discussed here:

And indeed the experience of others in the Bible. And Christians throughout the ages.

But the parable is surely particularly pertinent in the context of the events of the past five years or so.

One of the most striking things to me is that it matters very little who the person with the tape measure is. Or indeed how he or she acts. It is the very act of measuring, and the consequent pointing out of error that is unwelcome.

Whatever people might say, the reality is that most of us don’t like being wrong, and we don’t want to be seen to be wrong. This applies especially to those whose power and status becomes bound up a view that is shown to be wrong. It is embarrassing enough for anyone to admit that they have made mistakes. But for those in prestigious positions3 — including politicians, academics, senior managers, doctors, scientists, teachers and indeed church leaders4 — the prospect is particularly unappealing. Hard-earned reputations are at stake.

Given human nature, it would be understandable that any such people might — more than most — prefer that folk with tape measures were not there at all, or at least that they would keep quiet. It should thus not surprise us if those doing the measuring were regarded as being the problem. And/or if there were a concerted effort to simply ignore them.

But it should surely give us pause for thought if people who claimed to be “walking in the truth”5 were to respond in such a manner.

A crucial point about common knowledge

Back to the original post featuring the parable of the tape measure:

The [point] that isn’t obvious is the crucial point about *common knowledge*. Common knowledge is the mover here, not the truth. Only when the truth becomes common knowledge does it expose, obliterate, and humble Error. Let’s look at it more closely.

Common knowledge isn’t just what’s known; it’s what’s *known to be known*. This is a key and important difference in terms of motivating change. People will go with the crowd, or more often power (sometimes embodied in the crowd or consensus), most of the time.

That is, Error can flex its power, illegitimate as it may be, to convince people who have private knowledge of the truth to keep it quiet. People who measure the room or see it measured can be coerced to lie or stay silent or only whisper the truth to their friends quietly.

So long as the truth is not common knowledge, people will tend to follow power, even if its in Error, even if it’s just the lack of wisdom of the crowd, even if it’s led by nefarious forces (who might appear in sheep’s clothing). Private knowledge motivates no change.

When the truth becomes common knowledge, though, say by everyone seeing the measurement at the same time, only then is Error properly exposed, forcing change. In this case, all three “experts” are regarded as mistaken at best and frauds at worst.

In the moment when the truth (or even another Error) becomes common knowledge (or common belief, aka consensus), that new point of common knowledge will set the stage for what happens next. If it’s the truth, that's good, indeed righteous (see those deep lessons mentioned above).

If a new Error becomes common belief, however, you will have change that follows the new Error, which will also hate Truth to the degree that it is imbued with power and status that it wishes to keep, which will be high if the new Error was deliberately placed.

Are those words not worthy of careful — even prayerful — consideration?

I am reminded of how the apostle John records that:6

To the Jews who had believed him, Jesus said, ‘If you hold to my teaching, you are really my disciples. Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.’

Those words of Jesus — like all his words — were spoken into a particular situation, and one that is worth considering carefully, not least in the context of Error hating Truth. But the notion that the truth sets us free is surely widely applicable.

I am struck too by the fact that a key component of the gospel message is the call to repentance,7 which is surely not so very different from a call to admit Error and to acknowledge Truth. And if Christians — and particularly church leaders — will not admit error and acknowledge truth in the context of the past few years, I wonder what the implications are for any call to non-believers to repent.

I understand, not least from personal experience, that it can be embarrassing to have to admit mistakes. And that it is not always easy to acknowledge being fooled. But I see no alternative in the long run. As for those concerned about their reputations, surely it is better to address the issues sooner rather than later?

Moreover, until at least a substantial part of the truth of what happened during the covid era becomes common knowledge, it is difficult to see how the church at large can even begin to seek to discern why God brought about8 a situation where the vast majority of church buildings across the developed world were closed for months on end. Which might be an important question to think about.

Stepping back, one of my aims in posting on this Substack has been to help the truth about what really happened during the covid era become common knowledge.

In particular, I wrote [i] this two-part article with a view to putting the events of recent years in a broader context:

Though as with quite a few of my posts, I wonder whether that article came too early for many people, when the responses of doctors, wider society and churches in the covid era were still too much to contemplate.

I am reminded of the perceptive words of Charles MacKay, writing in 1841:

[People], it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one.9

And I wrote [ii] this letter — A suggestion for an apology in the context of the covid era — partly with the promulgation of truth in mind:

I was well aware at the time of writing (early 2024) that it might be months or even years before church leaders acted on it. But I was fairly sure that the evidence of damage from the covid response — which most church leaders (and members) accepted with very little pushback — would continue to mount. And I doubt very much that the issues raised, at least some of which are slowly but surely becoming common knowledge, are going to go away.

Dear Church Leaders articles (some of which can also be found on Unexpected Turns)

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered

A reference to the linked post at the start of this article

One of a trio of scholars who, in 2018, fooled scholarly journals into publishing hoax papers masquerading as legitimate scholarship

In the congregation of the church I attend there is an unusually high proportion of such people

I do of course recognise that these categories overlap somewhat

According to Matthew’s gospel, the first words in the public ministry of both John the Baptist (Matthew 3:2) and Jesus (Matthew 4:17) were: ‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near’

Or “allowed” if you prefer

From Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds