[SPCI-1] "It seems to me there was no need to depart from the usual response, except for shielding of higher risk groups"

Introduction to the Scottish People's Covid Inquiry; epidemiologist and public health medicine consultant Dr Alan Mordue on the Covid-19 public health measures

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

The recent Scottish People’s Covid Inquiry (SPCI, as distinct from the Scottish Covid Inquiry) featured several presentations that deserve a wide audience.

Over the next few weeks, I will post transcripts of links to the various presentations, along with additional comments here and there.

This first article features the self-explanatory introduction from Prof Richard Ennos, Professor of Ecological Genetics and now Honorary Fellow at the University of Edinburgh, followed by a presentation on public health measures during the covid era from Dr Alan Mordue, an epidemiologist who worked as a Consultant in Public Health Medicine.

Introduction

Link to video

I’d like to welcome you all on behalf of Common Knowledge to what I think is a groundbreaking conference, one in which the people of a nation interrogate what their national governments did during the time of covid in March 2020, possibly before then, and certainly after then.

Now this conference has in many ways been prompted by the official Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry. Here’s the website for that inquiry… and it is a rather typical government-led inquiry into what they did in 2020. And it’s very noticeable that a major assumption made at that inquiry, which is never questioned, is that there was a novel deadly respiratory disease present in Scotland in 2020, and they called it covid-19.

And, if you listen to the public inquiry, then they’re using the terms all the time: pandemic… they’re using term virus and they’re assuming that all of these things are actually present. And that the presence of these justified an unprecedented set of public health measures, including locking down and preventing people actually seeing one another during that time.

Effectively what they’re doing is marking their own homework. And what they want to do is to report back to ministers: “Okay, we did these things. Of course it was justified, but we need to learn a few lessons.” And that is I think is all that’s going to come out of that inquiry.

But what has actually happened is that very brave people have stood up, and they’ve said, “This is what happened to me as a consequence of the measures that you took.” And that has been very well publicised by Biologyphenom on his Substack. And it’s emerged just what levels of damage were caused. So that’s why we want this Scottish People’s Inquiry. It’s a people looking at their government and asking… the government what they did, why did they do it, what was the justification for it; and telling them about all of the damage that they did to their own people.

Here is Biologyphenom’s Substack:

There are many clips available from the Scottish Covid Inquiry, e.g. in this post.

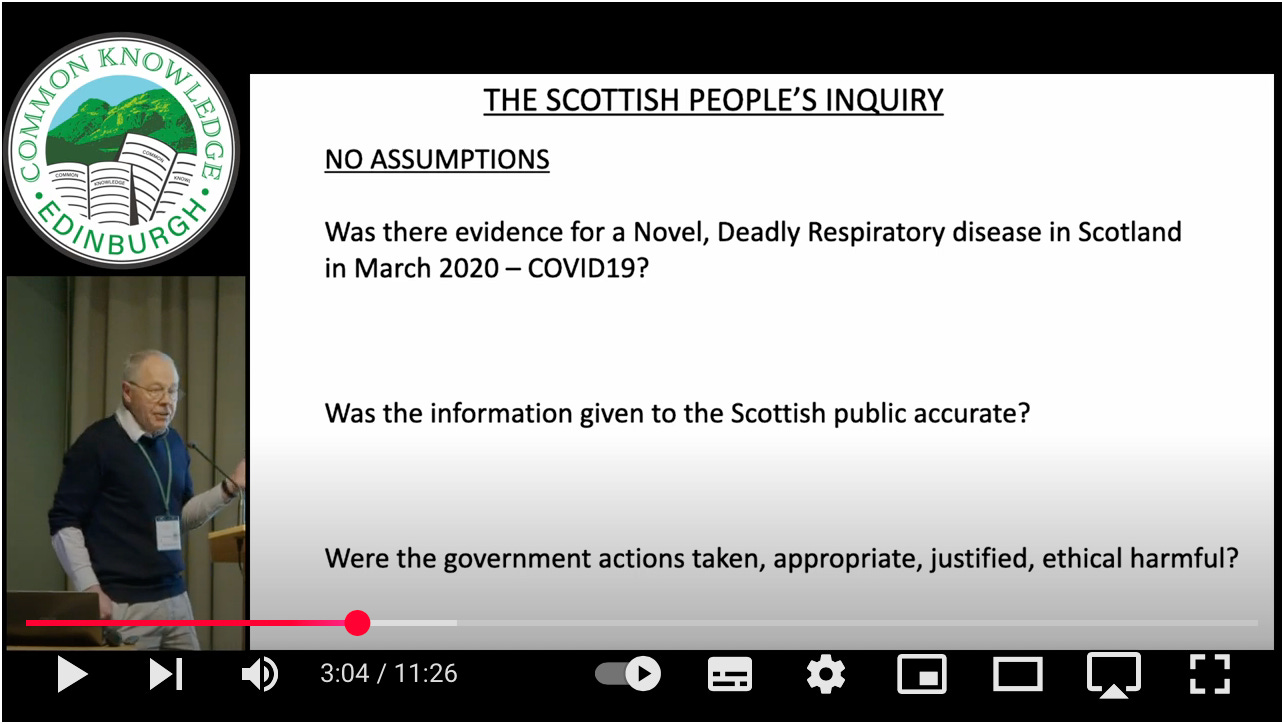

Major questions I want to have a look at during this conference are:

Was there actually any evidence for any novel deadly respiratory disease in Scotland in March 2020 as they said there was?

Was the information given to the Scottish public actually valid?

Was it accurate?

And, lastly, were the government actions which they took appropriate, justified, ethical or harmful?

Those are the questions I think I would like… to be addressed during this conference…

The [speakers] people come from different backgrounds, and they have different ways of looking at the at what happened… in… March 2020 and onwards. Their views are their views, and my views are my views, and it’s up to you to make up your own mind about what you think about those people’s views.

We’re not… telling you, “This is what you must think.” We’re telling you what happened as we see it, and you [can] make up your own mind about it.

First of all, I’m going to address the assumption that the official inquiry makes… that… their measures were justified because there was some novel, deadly respiratory disease — covid-19 — present in Scotland in March 2020 ,and therefore all of the measures they took in response were absolutely justified…

A few simple things… I don’t want to go into great scientific detail. I just want a common-sense view of these things.

First of all I go to the NHS website, and I find out… what is this disease that you call covid-19? What are its symptoms? And there are symptoms, and at the end the NHS says the symptoms are very similar to symptoms of other illnesses, such as colds and flu. Well, well, well…

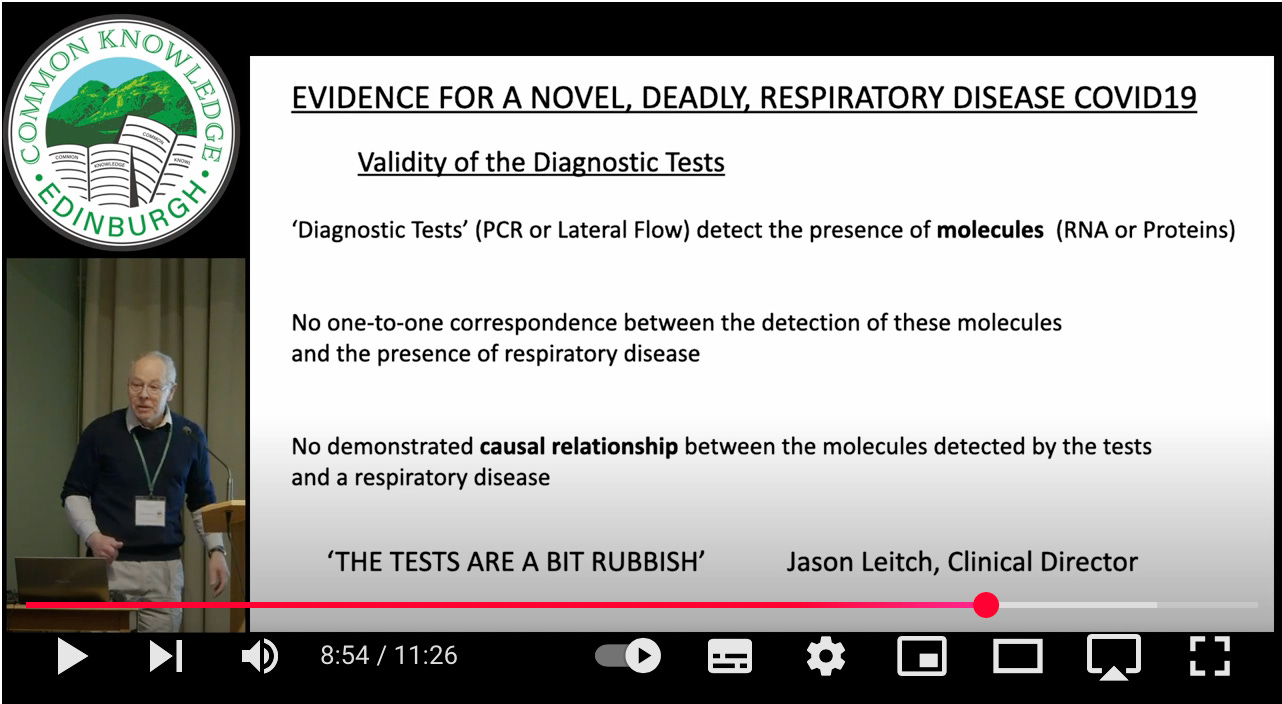

Oh, but you say… “Covid-19 does exist… we got a diagnostic test for it.” Yes, so what does a diagnostic test actually do? We’ve got PCR tests. We’ve got lateral flow tests. And they detect the presence of molecules… RNA or proteins. Unfortunately, there’s no one-to-one correspondence between the detection of these proteins or these RNAs and the presence of a respiratory disease.

So perfectly healthy people without a respiratory disease can test positive for this. So you can’t say this is a diagnostic test — it’s ridiculous. It’s testing for the presence of some molecules. And there is actually no demonstrated causal relationship between these molecules which are being detected and a respiratory disease. When people… have attempted to test people or infect them with these molecules… they don’t actually get any disease. So, in the words of Jason Leitch, the Clinical Director, “The tests are a bit rubbish”.

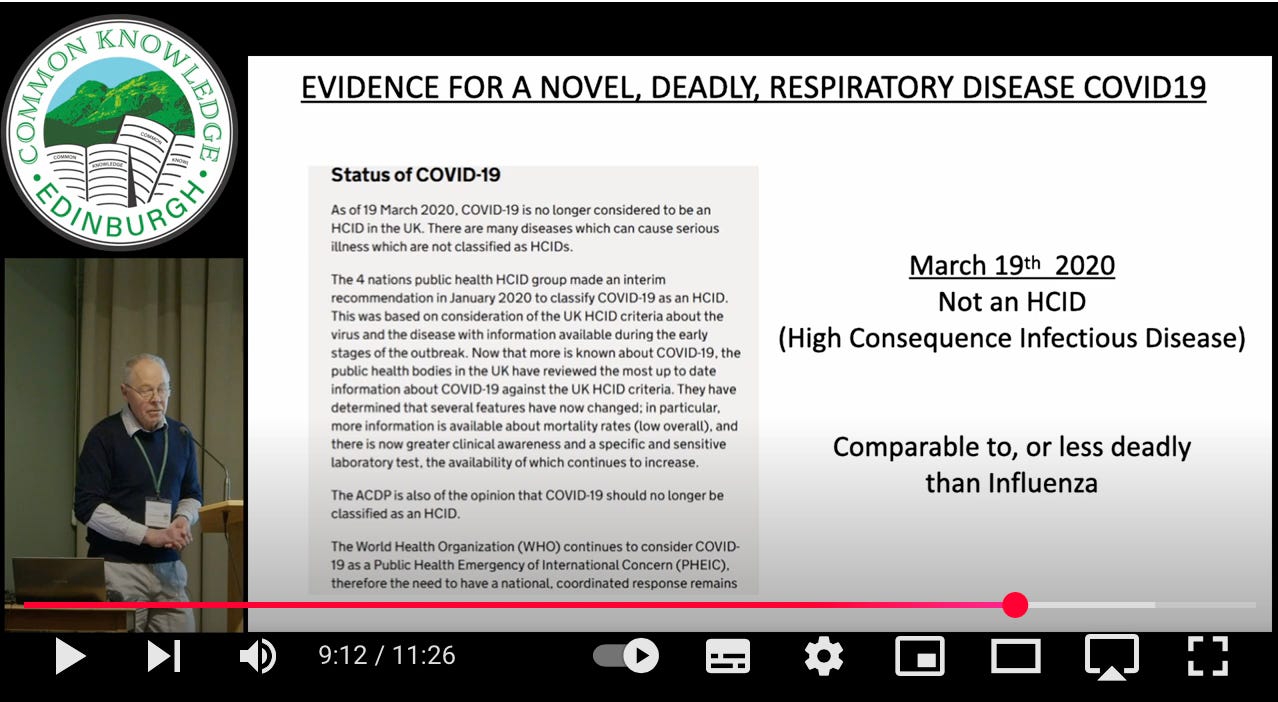

Lastly… suppose there was a disease… was it actually deadly? Well… in January 2020 it was declared a high-consequence infectious disease, but shortly before all the restrictions were imposed on the Scottish people it was downgraded — no longer a high-consequence infectious disease. And all four nations in the UK agreed upon that.

And when people have attempted to measure how serious this was, then what the figures that they come up with — which could be disputed — is that the seriousness of this disease is comparable to or less deadly than influenza, and doesn’t affect children.

So my conclusion from all this is that the evidence to support the presence of a novel deadly respiratory disease in Scotland in March 2020 was at best very weak. And my conclusion — and that’s my opinion — is that the imposition of unprecedented restrictions on the rights and freedoms of the Scottish public does not appear justified on this basis.

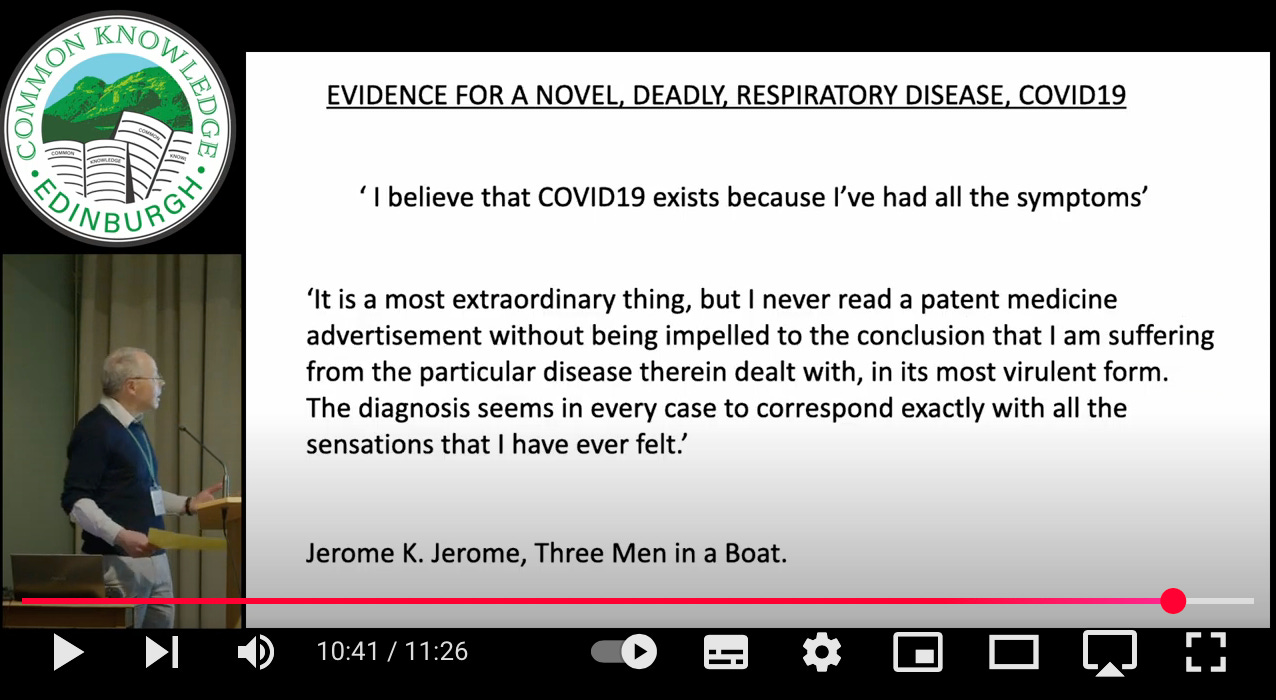

Just one more thing… I know that people say, “But I had it. I believe covid exists because I’ve had all the symptoms…” I’d just like to use this quote from Jerome K Jerome, who wrote Three Men in a Boat [published in 1889]:

“It is a most extraordinary thing, but I never read a patent medicine advertisement without being impelled to the conclusion that I am suffering from the particular disease therein dealt with in its most virulent form. The diagnosis seems in every case to correspond exactly with all the sensations I have ever felt.”

In 2009 there was even an article about Jerome K Jerome syndrome in the British Medical Journal:

The Covid-19 Public Health Measures (Dr Alan Mordue)

Link to video

Introduction

For the next 15 minutes I’m going to do a little time-travelling with you. I’m going to take you back five years to Spring of 2020… What I’m going to do is to address four key questions:

What was known about covid-19 — and I’m going to take at face value that there was a disease called covid-19, and I’m going to take at face value the official data that was coming out at the time, and then consider in the light of that, even… believing all of that, was it reasonable that we locked down… [that] we did what we did.

So the questions are:

What did we know about covid-19 in the spring of 2020? (And I’m using the 24th March, the first day of the first Scottish lockdown, as the cut-off point)

In the light of that information, was it true that we faced a health emergency?

What was the accepted approach to responding to pandemics? And what was in our pandemic plans?

And then I’m going to compare that with what we actually did

Question 1: What was known about covid-19 before the first lockdown on 24th March?

Well, there seemed to be a pneumonia of unknown origin identified in Wuhan in December 2019. Over the following weeks and months we learned more about the symptoms… which overlap with other respiratory diseases. We learned about the clinical signs and investigations, and a bit about treatment options too. And then, importantly, over that three month period, the Spring of 2020, data started to emerge about the mortality and what we call epidemiological characteristics.

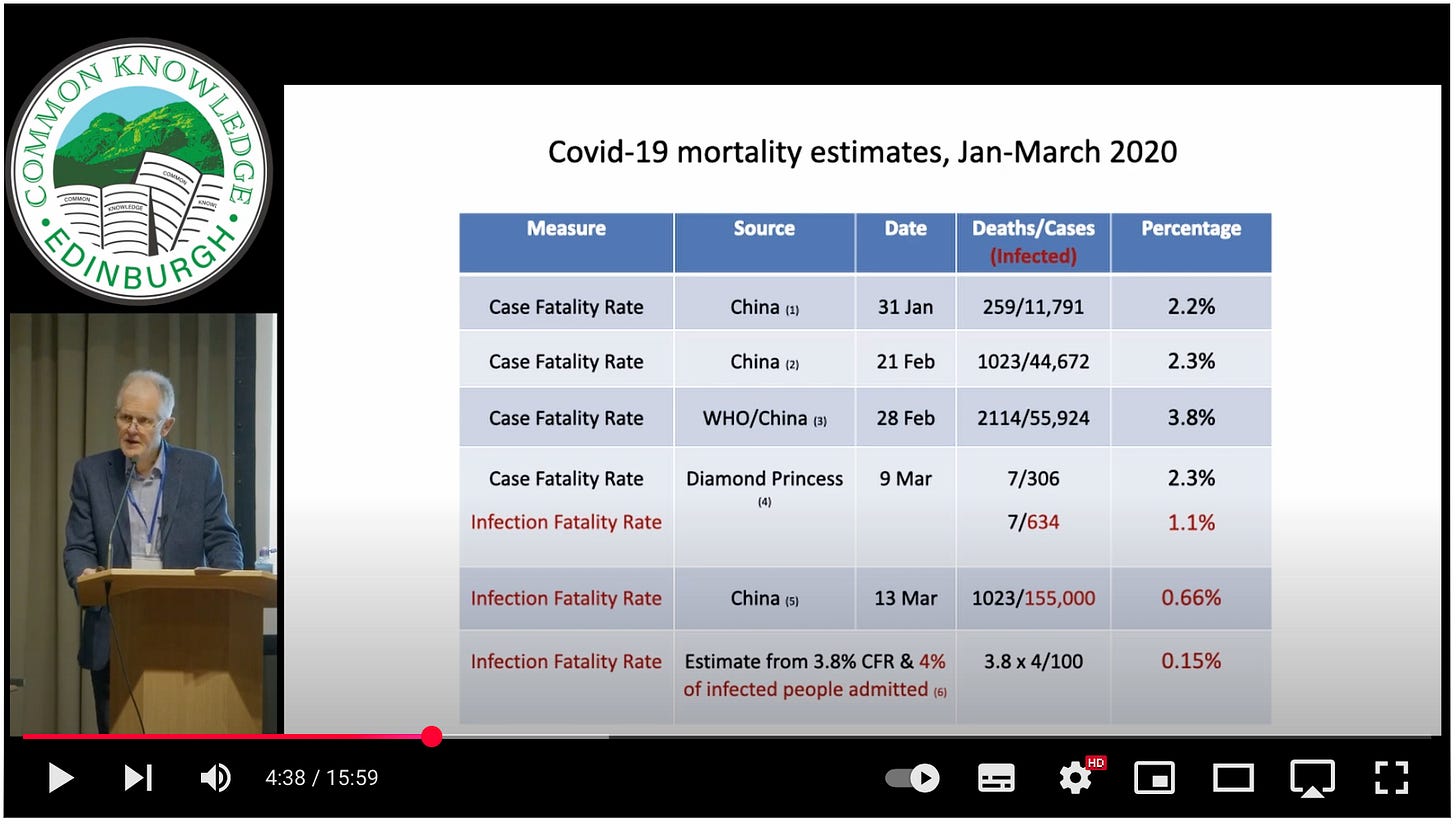

So this is the some of the mortality estimates… In the first line… there was a one-page report, the earliest I could find, which showed that the Chinese authorities had identified 259 deaths from about 12,000 cases, giving a case fatality rate of 2.2%. Three weeks later, more cases… more deaths unfortunately, but a similar case fatality rate. The third line there was the output from the WHO/China Joint Commission which reported at the end of February, and again more deaths, more cases in a slightly higher fatality rate.

And then at the bottom — I’m sure you remember the Diamond Princess, the cruise ship which was quarantined off a port in Japan — they noted seven deaths amongst 300 cases. And what’s helpful about Diamond Princess is that they also went on to do a lot more testing of passengers and the staff, but they came up initially with a case fatality rate very similar to the reports from China.

However, we need to understand the limitations of case fatality rates. They usually emerge when we have a new disease from hospitals. And they count the clinicians who recognise it in hospital… count the number of deaths… they count the number of cases then put one over the other and give us the case fatality rate. But what… that statistic doesn’t give us is potentially a far larger number of people out in the community with an infection… most of them have mild disease… they will never, hopefully, end up in hospital. So [a case fatality rate can give] us an inflated sense of the impact of any disease. What we really need to know is the infection fatality rate.

And the Diamond Princess… gave us the first estimate of the infection fatality rate, because… in their widespread testing amongst all passengers and staff, they identified another 300 infected people, which reduces the apparent mortality rate, and gives us the first estimate of infection fatality rate of 1.1%, less than half of the case fatality rate.

Then the Imperial team from London… looked at this and they produced another estimate of infection fatality rate using Chinese data… they estimated the infection prevalence within the Chinese population… and they came up with a rate of 0.66%.

And then the last line… there is my rough estimate. I’ve used the case fatality rate and then calculated an infection fatality rate using a figure that appears in the UK pandemic strategy. There they said between 1 and 4% of pandemic flu cases are admitted to hospitals, so I used that figure to arrive at this estimate — the lowest estimate, at 0.15%. And even if you assume 1 in 10 — not 4% but… 10% — of people with covid are admitted, you still only get to a infection fatality rate of 0.38%. So my conclusion from this is that the IFR is below 1%. Or, to look at it the other way around, 99% of people survive.

As noted e.g. here in this post, Prof Chris Whitty, the Chief Medical Officer for England, when taking questions from a UK Members of Parliament in early March 2020, stated that: “It is clear that the risk [of covid] is very heavily weighted towards older people.”

Footage here:

This data I’ve taken from the second Chinese reference. And they concluded that this disease was highly contagious. Most people have mild symptoms. They described the case fatality rate as low. And they noted that most deaths occurred in people over 60 and those with co-morbidities with chronic diseases. And you can see the youngest age group had a case fatality rate of 0.2%, the oldest 14.8%. But even in that… oldest group, about 15% succumbed, but 85% survived. And the co-morbidities… the highest was 10.5%… cardiovascular disease. Without any co-morbidity — 0.9%.

This chart on the right is taken from the very first Italian National Health Institute report, and it shows that men are at higher risk. This is the numbers of deaths, not the rates. Men are in blue and women in red. So men have a higher risk. And the other thing it shows is the very steep age stratification. So the three bars on the left you can hardly see… are below [age] 60. The four bars on the right are above 60. So… very few deaths below 60. And if you’re fortunate to be below 60 and not have any diseases, your risk is extremely low.

Question 2: Was there a health emergency?

One of the ways of… assessing this is to compare it with previous pandemics. So, on the top we have Spanish Flu which had an IFR of between 3 and 8%. Asian and Hong Kong flu were… far lower mortality rates… swine flu… below 2%.

However, moving to coronaviruses… SARS had a high case fatality rate… 3-28%… a huge variation in… the four countries that it appeared in. MERS — Middle East Respiratory Syndrome… 42% case fatality rate, extremely serious disease, IFR estimated to be 22%.

By comparison covid, particularly with an IFR below 1%… it’s certainly no Spanish flu… in terms of mortality rate… No SARS or MERS. It’s more like Asian or Hong Kong flu. So my conclusion is [that] if it was a health emergency, it wasn’t a dire one.

Question 3a: What was the accepted approach to pandemic measurement? (Measures to reduce transmission)

I’m going to take [this] in two sections…

This slide looks at measures to reduce transmission. These are the standard public health measures for respiratory viruses — respiratory and hand hygiene… cough or sneeze into a tissue… afterwards discard it, wash your hands. Isolate those with symptoms to stop onward transmission to others. Contract tracing not thought to be effective — not much evidence for that, except in the very earliest phases. Mask-wearing only for healthcare staff. Potential school closures early on but not thereafter. And that’s simply because, in flu, children are known to be super spreaders — not evidence of that with covid-19. Accurate public health messaging so we avoid panic — we’ll hear a bit from Diane [Rasmussen] about whether we were successful in doing that [Laughter].

Tailored messaging for at-risk groups, high-risk groups… [the pre-covid recommendations] didn’t amount to shielding or focused protection… it fell short of that. These measures were based upon evidence… upon systematic reviews of the evidence like the Cochrane review on the top right, and the WHO review on the bottom right. And that WHO review was published in Autumn 2019, just a few months before the pandemic started.

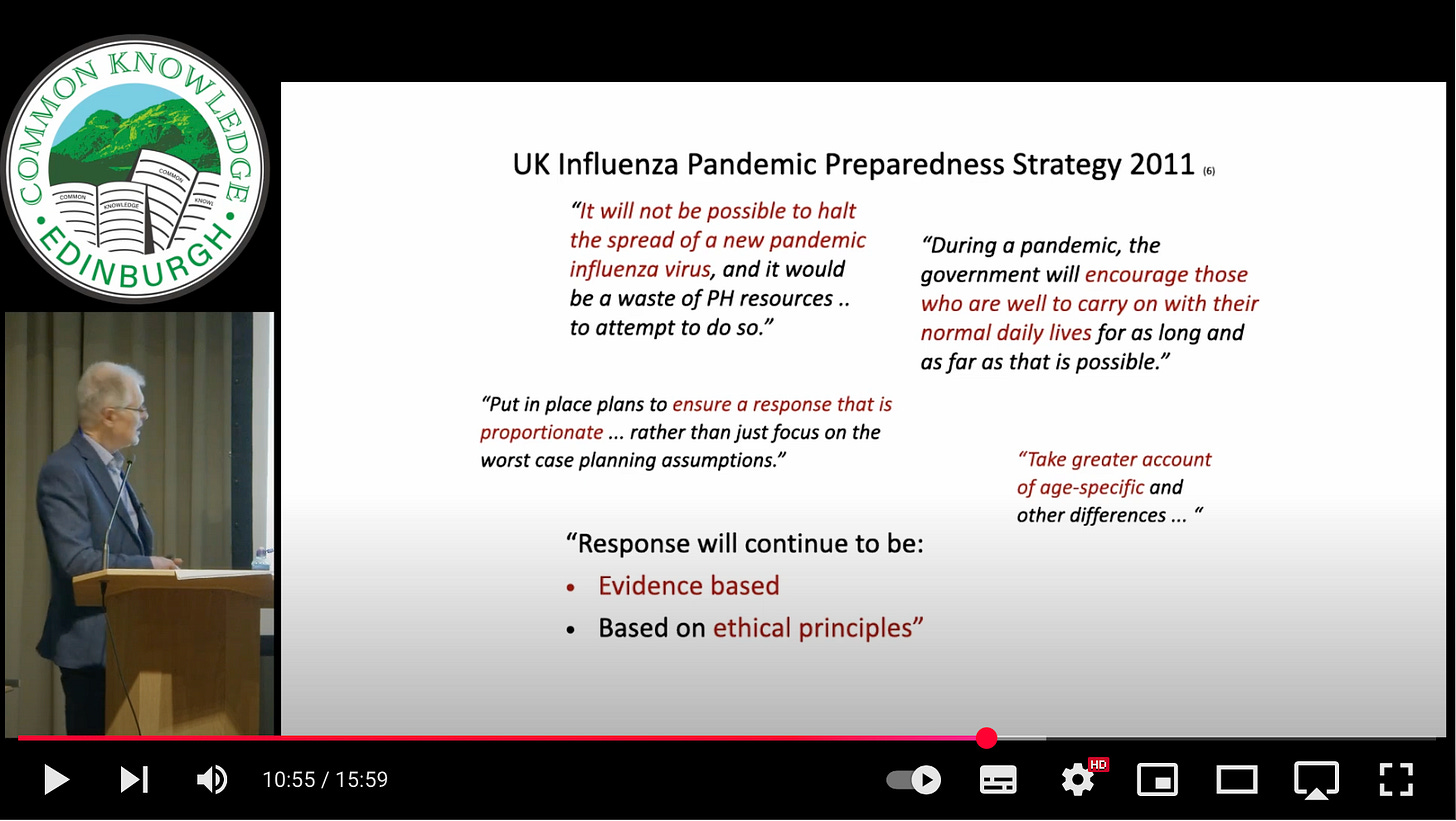

Some quotes from the UK pandemic strategy [the UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy 2011] to give you a flavour of this document:

It won’t be possible to halt the spread of a pandemic flu virus

During a pandemic we encourage those who are well to carry on as normal

We need to put in place plans and responses which are proportionate

We need to take greater account of age-specific differences

And last…

The response will be evidence-based, and based on ethical principles

Well, we’ll hear a bit more about evidence from Clare [Craig] later on today, and ethical principles from Liz [Evans]

Question 4: What measures were taken during the covid-19 response?

How did we do on the measures to reduce transmission compared to what was in our plans?

The hygiene measures were straightforward. Isolation… we went way beyond isolating those with symptoms. We isolated everyone with a positive test, and there are problems, as we heard from Richard [Ennos, in the introduction] with this test. In certain phases of the pandemic there were certainly far more false positives than real true cases. So we were isolating people when we didn’t need to do that.

It was when the government refused to disclose the official false positive rate that I first knew for sure that something bad was going on. The Department of Health’s Lord Bethell stated, in a written Parliamentary answer in October 2020, at least six months after covid PCR testing had been introduced, that “the United Kingdom operational false positive rate [for the PCR test] is unknown”.

For more context on the PCR test, see e.g. this post featuring Kary Mullis, winner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method”, and who around that time stated that, “with PCR… you can find almost anything in anybody”:

We had very widespread contact tracing despite evidence. And that continued for most of the pandemic. And we isolated cases too… So we were isolating thousands and thousands of people unnecessarily. And then we advocated general community mask-wearing even for children who weren’t at significant risk… and social distancing.

We closed schools and we closed universities, having huge impacts on education… Being diplomatic… the information to the public wasn’t always accurate. The content wasn’t always appropriate as well, and certainly it did raise concerns and alarms. We shielded people in the high-risk groups which was very good, but we went on to lock down businesses, society and people and the NHS. And without a cost benefit analysis. So we went well beyond the pandemic plans.

You’ll remember the daily broadcasts from Nicola Sturgeon and Boris Johnson, the endless charts from Whitty and Vallance. Whenever you went out of the house you were conscious of the police watching you… empty roads… And, in Northern Ireland — you won’t be aware of this one — they even had social distancing for cars. [Laughter]

So [coming back to]…

Question 3b: What was the accepted approach to pandemic measurement? (Measures to protect and treat individuals)

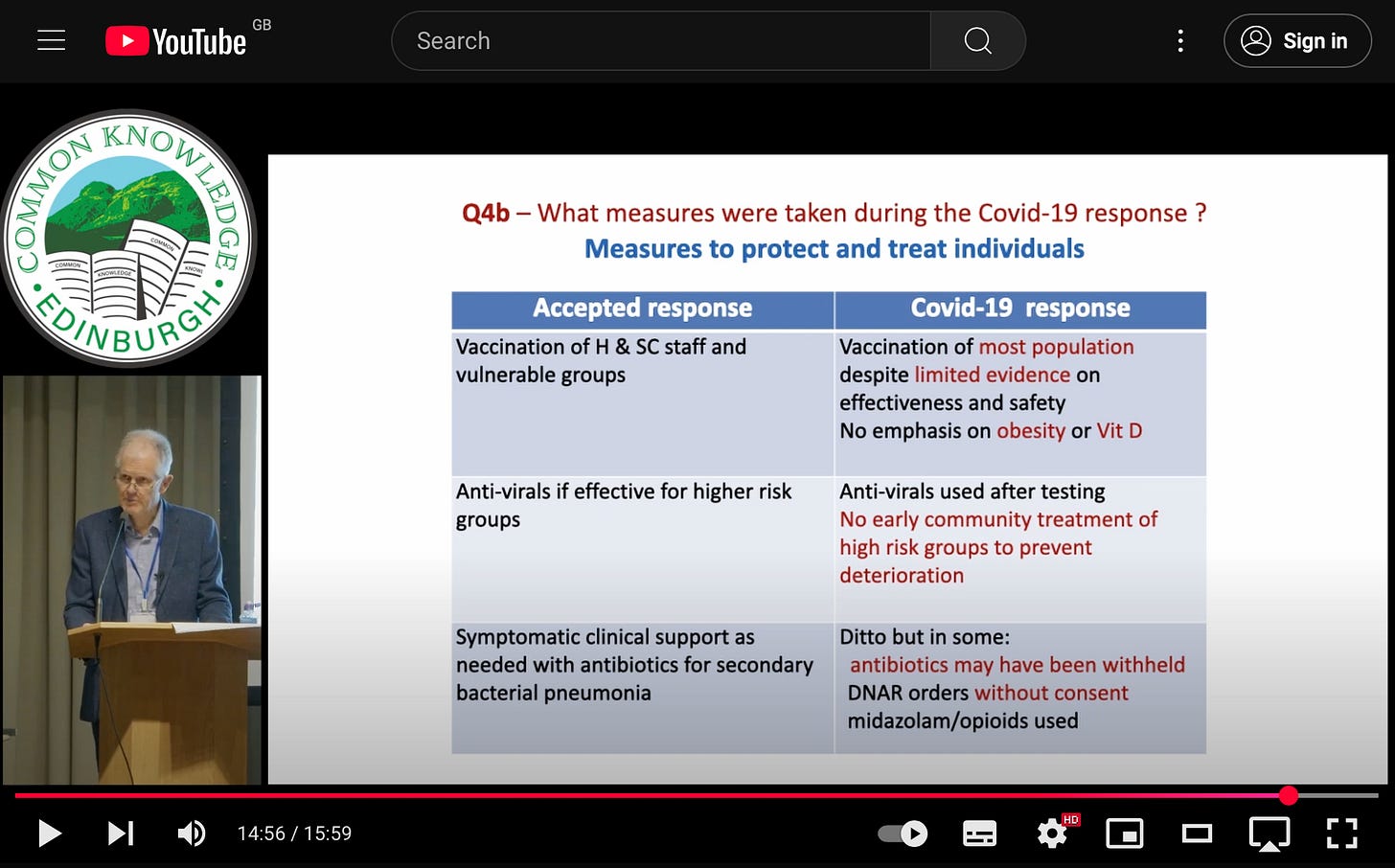

Traditionally, what we did was we vaccinated health and social Care staff, and vulnerable groups. If we had evidence, we gave antivirals to at-risk groups. And we provided symptomatic support in hospital, particularly for those with serious illness, including antibiotics for secondary prevention.

By comparison, in the actual covid response, we vaccinated virtually the whole population, despite not having very good evidence on effectiveness nor safety. We didn’t emphasise that obesity increases risk, or [that] vitamin D might reduce risk. We did use antivirals, but we didn’t use repurposed drugs for early treatment to prevent deterioration, despite having moderate quality evidence that they were effective.

Studies on repurposed drugs can be found e.g. here:

And then coming to the symptomatic support, we provided that, but we didn’t always provide antibiotics for secondary bacterial infection. We applied “Do Not Resuscitate” orders, without consent in some cases. And we used midazolam and morphine perhaps when we shouldn’t have done. So, significant departures…

Conclusions

So these are my conclusions:

Early case fatality rate estimates were around 2.3% but IFR much lower — below 1%.

High-risk groups were clearly defined, so most people weren’t at risk.

And therefore it seems to me there was no need to depart from the usual response, except for shielding of higher risk groups.

And I just wanted to emphasise the last point… that the accepted responses [prior to 2020] were evidence-based and lockdown harms were actually predicted.

Links to the other posts in the series:

#1 Alan Mordue | #2 Diane Rasmussen McAdie | #3 Richard Ennos | #4 Alison Walker

#5 Pam Thomas | #6 Bill Jolly | #7 Martin Neil | #8 Liz Evans | #9 Clare Craig

Dear Church Leaders most-read articles

Some posts can also be found on Unexpected Turns

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered as the solution to a problem