That Hideous Strength: a deeper look at how the West was lost

Reflections on a book written before the covid era, and the lessons we can learn from communist Eastern Europe

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

I recently finished reading That Hideous Strength: a deeper look at how the West was lost by Melvin Tinker, vicar of St John’s Newland in Hull.

The copy I have is an expanded version of the 2018 original, as detailed in the blurb here:

In 2018 EP [Evangelical Press] published the original That Hideous Strength: how the West was lost; the book originated as lecture notes author Melvin Tinker prepared for a conference in Jerusalem that year.

That edition deliberately had no footnotes and was as compact as possible to appeal to a wide audience. There have been many requests for a footnoted and expanded edition.

The text above looks like it was written by the publisher. The next part looks as though it might have been written by the author:

This book is an expanded version of the previous edition — it is about a third larger. The original acted as a ‘primer’ and ‘wake-up call’ to enable Christians especially to try and understand what has been happening in our Western culture for the last few decades due to the influence of what is identified as ‘cultural Marxism’ or ‘Critical Theory’. Many commented that it helped them make connections not seen before; for others, it was an ‘a-ha moment’, with the light suddenly being switched on as to why much of the Judeo-Christian foundations of the West have been eroded while the Church sleeps A number of reviewers rightly said it would have been helpful to have had the works quoted referenced and expanded with footnotes that has now been corrected.

As well as unpacking in more detail some of the ideas of cultural Marxists and the way their strategies are being worked out in our society, I have also sought to put more flesh on what the Church’s response might look like by drawing attention to what has been called ‘the Benedict Option’ and developing the concept proposed by Charles Taylor — the ‘social imaginary’. Another significant addition is an outline of the ideas of classical Marxism which places the current concern for cultural Marxism in its proper historical and philosophical context. It also serves to underscore that in many ways the ‘new Marxism’ is a revamping of the ‘old Marxism’ with consequences no less disastrous.

That Hideous Strength in 2020

A new totalitarianism is being introduced into Western society

I read the book with interest and I recommend it to any Christian concerned with current trends in society.

I was particularly struck by this paragraph in the Preface (p19):

In the course of this book I shall give some disturbing examples of the way a new totalitarianism is being introduced into Western society and the way the Church has colluded with this — at times actively, by buying into cultural Marxism (theological liberalism), or passively, by not concerning itself with such matters so long as one can be left to preach the Word (evangelical pietism). The picture which will be painted will be a bleak one, but, I trust, realistic. [Emphasis added]

I found the examples that Tinker goes on to give — not least in the context of what he calls The Gender Agenda, the title of the fourth of his six main chapters — to be consistent with his claim.

Unsurprisingly, given the title, Tinker’s That Hideous Strength draws on the 1945 novel of the same name by C. S. Lewis, which was the final novel of The Space Trilogy. It has evidently had more than a few covers in its time:

The account of the Tower of Babel also features heavily, which was of particular interest to me in the context of this article that I posted a couple of weeks ago:

For me, two particularly notable parts of the Tinker’s That Hideous Strength were:

[i] His description of Justin Welby as a “useful idiot” (p109) in the context of a lecture the Archbishop gave in Moscow in 2017:1

It is obvious that the Archbishop wants to defend and strengthen the place of the family in society, but by implying that biblical norms regarding what constitutes family are too ‘narrowly defined’, Welby unthinkingly falls into line with the neo-Marxist drum beat that the family is a malleable concept which can (and should) be changed or even got rid of altogether, thus making himself a ‘useful idiot’.

[ii] A warning to evangelicals in the Church of England (and other denominations) (p153):

Earlier [in the book] attention was drawn to parallels between Christians living in pre-war Nazi Germany and our present situation: this also holds for the [easygoing] manner some evangelicals are adopting towards the Church of England as it blithely embraces the new norms of the secular culture. Here we have Gustav Heinemann writing in 1938:

‘We have done nothing to awaken a genuine and credible readiness to give up the official church… How much have we declared unbearable, and yet we bear it… We are neither as an organisation nor as individuals prepared for anything other than that which we have had for generations… In the best case, we are waiting for a great and utterly unignorable signal to break away. It will not come. There will only be signals in small doses, which will not bring us to a complete break.’

Similarly, there will be no unignorable signal for those in the mixed denominations in which the ‘hideous strength’ continues to exercise its power. [Emphasis added]

But I suspect that it is Tinker’s thoughts on an essay by Václav Havel2 that will stay with me longest.

The compliant greengrocer

Tinker quotes at length from Havel’s The Power of the Powerless which is available for download here (with direct link to pdf here).

In his fifth chapter, Barbarians Through the Gates (p125), Tinker writes:

If… we are now all in ‘Marx’s world’ and heirs to a revolution brought about by cultural Marxism, then we might be helped to understand the nature of that dominant social imaginary and how we might work towards its change by listening to someone who, for many years, lived under such a system. One person who has much to teach us is the late Václav Havel.

Havel was one of the leading members of the Charter 77 Movement which led to the ‘Velvet Revolution’ in Czechoslovakia in 1989. Their motto was ‘Live the Truth.’ Eleven years earlier, in 1978, Havel wrote a deeply insightful essay, ‘The Power of the Powerless.’ In it he described the communist system which held most of Eastern Europe in its iron grip as a ‘post-totalitarian system’ to distinguish it from traditional dictatorships. This was a ‘dictatorship of a political bureaucracy over a society which has undergone economic and social levelling.’3 The bureaucracy enforces and maintains an ideology, in this case Marxism, which is attractive to the citizens in that it provides some sort of cohesion to life, giving the individual an identity derived from the system. There is, however, a high price tag attached, namely, the ‘abdication of one’s own reason, conscience, and responsibility, for an essential aspect of this ideology is the consignment of reason and conscience to a higher authority.’4

He then asks:

How does such a post-totalitarian society acquire well-meaning citizens, who, if asked and allowed to express themselves freely, would not countenance such an ideology and society for a moment, to conform and, more than that, collude with ‘the system’?

And explains:

To answer that question, Havel employs a homely illustration. He asks us to imagine a scene where a greengrocer places a sign in his shop window amidst the carrots and onions. The sign reads: ‘Workers of the world unite!’ Havel then asks: What is the greengrocer trying to communicate by doing such a thing? Is it that he is personally enthusiastic about the idea and, therefore, this action expresses his socialistic fervour? Havel suggests not. He does it, maintains Havel, because he has been asked to do it and has been doing it for years as have countless other shopkeepers — everyone does it. And that is the point — everyone does it. The slogan, argues Havel, is a sign containing:

‘a subliminal but [very] definite message. Verbally, it might be expressed this way: “I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.” This message, of course, has an addressee: it is directed above, to the greengrocer’s superior, and at the same time it is a shield that protects the greengrocer from potential informers.’5

Havel points out that if the [green]grocer were given a sign stating this unambiguously, he might even put up such a sign, but would be ashamed to do it:

‘To overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on its textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the greengrocer to say, “What’s wrong with the workers of the world uniting?” Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. It hides them behind the facade of something high. And that something is ideology.’6

An ideology, according to Havel, is ‘a specious way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of an identity, of dignity, and of morality while making it easier for them to part with them.’

The point of the grocer displaying the sign in the window is not that it has to be taken literally, but the subtext is certainly meant to be taken seriously — for the display[s] of such signs are ‘givens’ of the rules of the game. Displays of loyalty are expected, and any form of dissent — such as an unwillingness to display such signs — will not be tolerated. Not just by the higher powers, but by the other shopkeepers and workers like himself. They may not be any more devoted as Marxists than he is, but by failing to engage in displays of loyalty like this one, they endanger throwing the accepted social order into disarray. This may sound rather dramatic, but as Havel points out such public and tightly visible symbols of loyalty and conformity are ‘part of the panorama of everyday life.’ 7 The details of the particular sign can be ignored, but its significance lies in the fact that it contributes to the panorama of signs and symbols and the ‘PC language’ which is all around.

‘This panorama, of course, has a subliminal meaning as well: it reminds people where they are living and what is expected of them. It tells them what everyone else is doing, and indicates to them what they must do as well, if they don’t want to be excluded, to fall into isolation, alienate themselves from society, break the rules of the game, and risk the loss of their peace and tranquility and security.’8

Remember, Havel is describing communist Czechoslovakia. But a moment’s reflection soon reveals that, with a few minor changes of detail, he could be describing much of Western Europe and North America where its citizens are expected — on pain of social ostracization, loss of job, or even imprisonment — to display a similar loyalty to the cultural Marxism of our day.

Signs in shop windows declaring ‘Workers of the world unite’ may not be required in the UK, but signs celebrating [Pride Month] most certainly are. Let a manager of a local Sainsbury’s store refuse to display such a sign and see what happens. Police stations, universities, town halls, and even cathedrals are expected to fly the rainbow flag and woe betide any transgressor who desists. National Trust employees, and, in some cases, teachers, are expected to wear rainbow lanyards that month and dissenters are made to feel uncomfortable at the very least. Like Havel’s greengrocer, very few of those who kowtow actually have any firm convictions about so called ‘gay rights’, but they know what is expected of them and they also know what to expect if they don’t conform.

The principled greengrocer

In his sixth and final chapter Bringing Down Babel, Tinker writes, in the context of The Power of the Powerless and what it is like to live in what Havel called a ‘post-totalitarian’ society (p162):

The parallels with our society are self-evident. The pressure to conform and collude with the prevailing Zeitgeist, in our case cultural Marxism, is real. It is all too easy to become like the greengrocer in Havel’s illustration, succumbing to ‘keeping our heads down and mouths shut’ and agreeing to ‘virtue signal’ when it is required of us. But there is another option which Havel explores.

He asks us to further imagine that one day the greengrocer snaps and decided not to put up slogans as was expected of him. More than that, he finds it within himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support. What is actually happening here? Havel states that the grocer is doing something highly significant and powerful. He is ‘stepping out of living within the lie […] His revolt is an attempt to live the truth.’9 In other words, he refuses to play the game, and, in so doing, disrupts the game:

‘The greengrocer has not committed a simple, individual offense, isolated in its own uniqueness, but something incomparably more serious. By breaking the rules of the game, he has disrupted the game as such. He has exposed it as a mere game. He has shattered the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the system. He has upset the power structure by tearing apart what holds it together. He has demonstrated that living a lie is living a lie. He has broken through the exalted facade of the system and exposed the real, base foundations of power. He has said that the emperor is naked. And because the emperor is in fact naked, something extremely dangerous has happened: by his action, the greengrocer has addressed the world. He has enabled everyone to peer behind the curtain. He has shown everyone that it is possible to live within the truth.’10

Havel goes on to envision something even greater sprouting from this small mustard seed of non-conformity: the growth of a movement. This resulted in the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of 1989 and the total collapse of communism in his country.

‘The greengrocer may begin to do something concrete, something that goes beyond an immediately personal self-defensive reaction against manipulation, something that will manifest his newfound sense of higher responsibility. He may, for example, organize his fellow greengrocers to act together in defense of their interests. He may write letters to various institutions, drawing their attention to instances of disorder and injustice around him. He may seek out unofficial literature, copy it, and lend it to his friends.’11

He describes these actions as ‘elementary revolts against manipulation: you simply straighten your backbone and live in greater dignity as an individual.’ This is ‘living the truth’ — an inner freedom which works itself out at a cost:

‘[In the wider world] its most important focus is marked by a relatively high degree of inner emancipation. It sails upon the vast ocean of the manipulated life like little boats, tossed by the waves but always bobbing back as visible messengers of living within the truth, articulating the suppressed aims of life.’12

He does not envision some political organisation to bring this about, but each person ‘living the truth’ over and against ‘the lie’ in their own spheres of influence of life. This would then develop what the Czech Ivan Jirous described as a ‘second culture’ which:

‘very rapidly came to be used for the whole area of independent and repressed culture, that is, not only for art and its various currents but also for the humanities, the social sciences, and philosophical thought. This second culture, quite naturally, has created elementary organizational forms.’13

Havel goes on to suggest not a complete withdrawal from society, but an engagement with it not least by setting up parallel structures in which the second culture can flourish without completely withdrawing from society. These would then point in another direction and, in so doing, establish cultural points in preparation for when the post-totalitarian society eventually disintegrates.

It doesn’t take that much of a leap of the imagination to see how this translates with some ease to the situation in the West and particularly the call for Christians who are people of the Truth to live the truth (1 John 1:6). It neatly fits with what we have been exploring in this section, namely, what it means to ‘be against the world in order to be for the world.’ The biblical imagery provides the emancipation spoken of by Havel whilst the Holy Spirit provides us with the courage to live as exiles and pilgrims or, to employ Havel’s illustration again, ‘non-conformist grocers’.

In the final pages of the main part of the book, Tinker then discusses (p165ff) the ‘Benedict Option’14 — the proposal from Rod Dreher in this 2018 book:

…[that] a Westernised form of ‘antipolitical politics’, to use the term coined by Czech political prisoner, Václav Havel, is the best way forward for Orthodox15 Christians seeking practical and effective engagement in public life without losing integrity, and indeed, our humanity.16

That Hideous Strength in 2024

The timing of Tinker’s expanded edition of his 2018 book is worth noting. In the Postscript chapter at the end of the book, he writes:

Having completed the major part of this book events have taken place on a global scale which depict a vigorous unleashing of “that hideous strength” we have been considering.

As I write, the seismic effects of the disturbing death of George Floyd in Minneapolis in June 2020 are being acutely felt, particularly in the West… [Emphasis added]

There is little mention of the covid era in the Postscript, and (as far as I recall) none in the rest of the book. Which is not too surprising given that the original text was written in 2018, and the major part of the expanded version apparently finalised by June 2020, at which time the small minority of people who regarded covid as anything like a vehicle for advancing cultural Marxism were widely viewed as “conspiracy theorists”.

In short, all of what I have quoted from Tinker’s book was essentially written pre-covid. Which to my mind makes it all the more interesting to read in the context of subsequent events. In the remainder of this article, I will consider some of the arguments of Tinker (and Havel) in the context of the past few years.

A new totalitarianism was introduced into Western society

Returning to the paragraph in the Preface (p19)…

In the course of this book I shall give some disturbing examples of the way a new totalitarianism is being introduced into Western society and the way the Church has colluded with this — at times actively… or passively, by not concerning itself with such matters so long as one can be left to preach the Word… [Emphasis added]

…something similar could be written about the covid era, which surely provides a particularly compelling example of a way in which a new totalitarianism was (at least for a time) introduced into Western society where the Church colluded.

To anyone who still doubts that, I recommend reading this two-part article:

And this post:

It is striking that, even now, few church leaders seem able to recognise what happened for what it actually was, let alone to acknowledge it publicly.

Those at the church I attend appear reluctant — to say the least — even to engage with the evidence, which can be done without any expertise. It would appear that, to paraphrase Tinker, they do not want to concern themselves with such matters so long as they can be left to preach the Word.

I am less than convinced of that approach myself though, not least in the context of what Rev Dr William Philip says in the podcast featured in this post:

The man in the cloth mask

Let us now return to Tinker’s Barbarians Through the Gates (Chapter 5) and Václav Havel’s essay The Power of the Powerless.

To paraphrase (both Tinker and Havel):

How does… society acquire well-meaning citizens, who, if asked and allowed to express themselves freely, would not countenance such extreme health measures for a moment, to conform and, more than that, collude with ‘the system’?

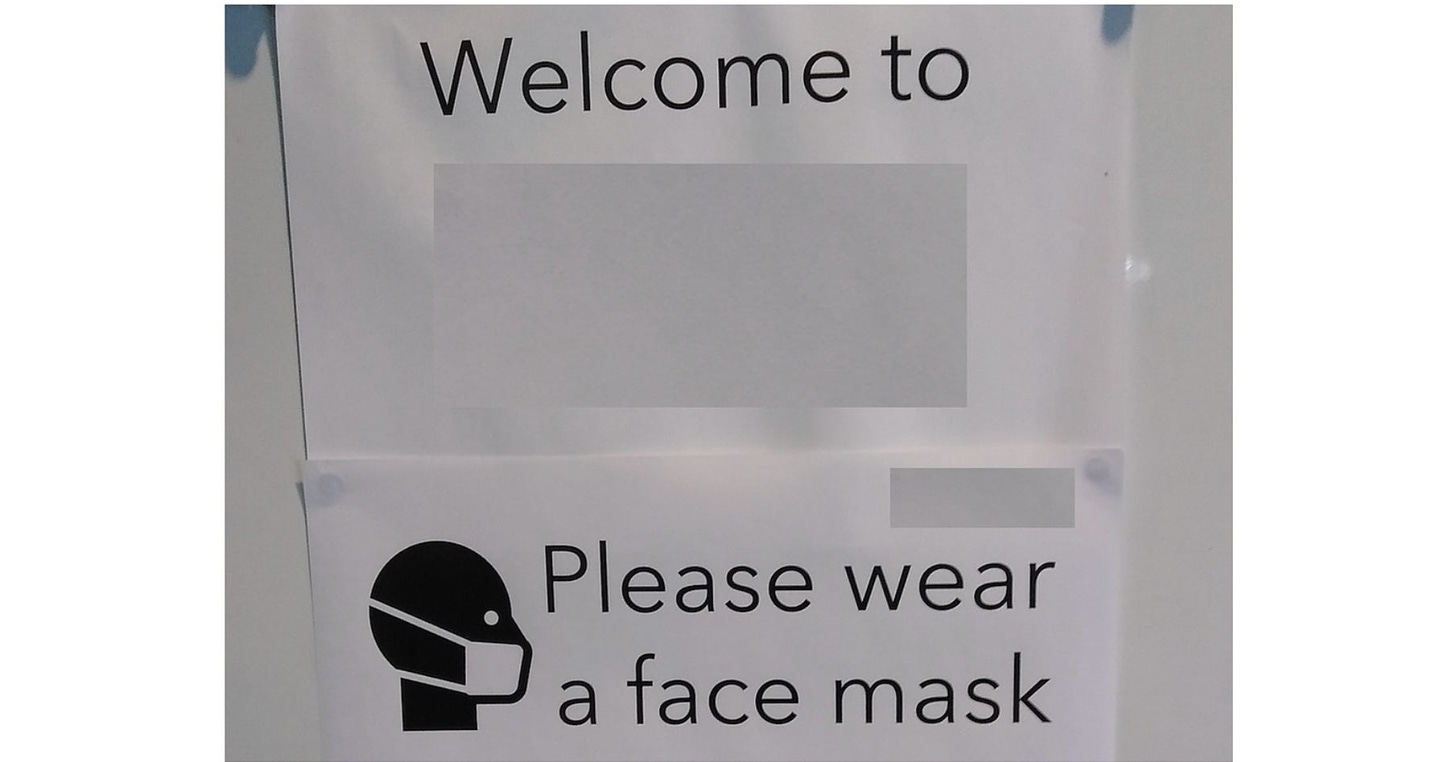

To answer that question… imagine a scene where a man covers his face with a cloth mask when he goes to church. What is he trying to communicate by doing such a thing? Is it that he is personally enthusiastic about the idea and, therefore, this action expresses his enthusiasm for draconian and unprecedented public health measures?

Perhaps. But perhaps not. He does it because he has been asked to do it and has been doing it for weeks as have countless others — everyone does it. And that is the point — everyone does it. As the behavioural scientists know all too well, the mask sends this subliminal but very definite message (among others): “I am a law-abiding citizen and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.” This message, of course, has an addressee: it is directed above, to those charged with enforcing the rules, and at the same time it is a shield that protects against potential informers.

If the man were given a badge to wear stating this unambiguously, he might even agree to wear it, but would be ashamed to do it. And so to overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on the face of it (no pun intended) indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the man to say, “What’s wrong with taking sensible precautions for the benefit of others?” Thus the mask helps the man to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. It hides them behind the facade of something high. And that something is ideology, which, according to Havel, is a specious way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of an identity, of dignity, and of morality while making it easier for them to part with them.

The point of the man wearing the mask is not that it actually has anything to do with health, but the subtext is certainly meant to be taken seriously — for the displays of such signs are ‘givens’ of the rules of the game. Displays of loyalty are expected, and any form of dissent — such as an unwillingness to wear a mask — will not be tolerated. Not just by the enforcers, but by other members of the public.17 They may not be any more devoted to draconian public health measures than he is, but any failure to engage in displays of loyalty like this one risks throwing the accepted social order into disarray. This may sound rather dramatic, but such public and tightly visible symbols of loyalty and conformity are part of the panorama of everyday life in a “pandemic”. The exact nature of the mask can be ignored. Its significance lies in the fact that it contributes to the maintenance of the pandemic narrative which says that we are all in danger.

This panorama, of course, has a subliminal meaning as well: it reminds people what is expected of them. It tells them what everyone else is doing, and indicates to them what they must do as well, if they don’t want to be excluded, to fall into isolation, alienate themselves from society, break the rules of the game, and risk the loss of their peace and tranquility and security.

While the above example concerns masks, a moment’s reflection soon reveals that, with a few minor changes of detail, it could also be applied to e.g. vaccination status, where citizens are expected — on pain of social ostracization or even the loss of a job — to display a similar loyalty to the public health narrative.

The power of the powerless

And finally, let us return to Tinker’s sixth and final chapter Bringing Down Babel.

Again, to paraphrase (Tinker and Havel):

The parallels with our society are self-evident. The pressure to conform and collude with the prevailing Zeitgeist, in this case wearing a mask (and/or getting a vaccine) is real. It is all too easy to become like the man in the illustration, succumbing to ‘keeping our heads down and mouths shut’ and agreeing to ‘virtue signal’ when it is required of us. But there is another option.

Imagine that one day the man snaps and decides not to wear the mask that is expected of him. More than that, he finds it within himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support. What is actually happening here? The man is actually doing something highly significant and powerful. He is stepping out of living within the lie that masks “help keep people safe”.1819 His revolt is an attempt to live the truth. In other words, he refuses to play the game, and, in so doing, disrupts the game.

The man has not committed a simple, individual offence, isolated in its own uniqueness, but something incomparably more serious. By breaking the rules of the game, he has disrupted the game as such. He has exposed it as a mere game. He has shattered the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the system. He has upset the power structure by tearing apart what holds it together. He has demonstrated that living a lie is living a lie. He has broken through the exalted facade of the system and exposed the real, base foundations of power. He has said that the emperor is naked. And because the emperor is in fact naked, something extremely dangerous has happened: by his action, the man has addressed the world. He has enabled everyone to peer behind the curtain. He has shown everyone that it is possible to live within the truth.

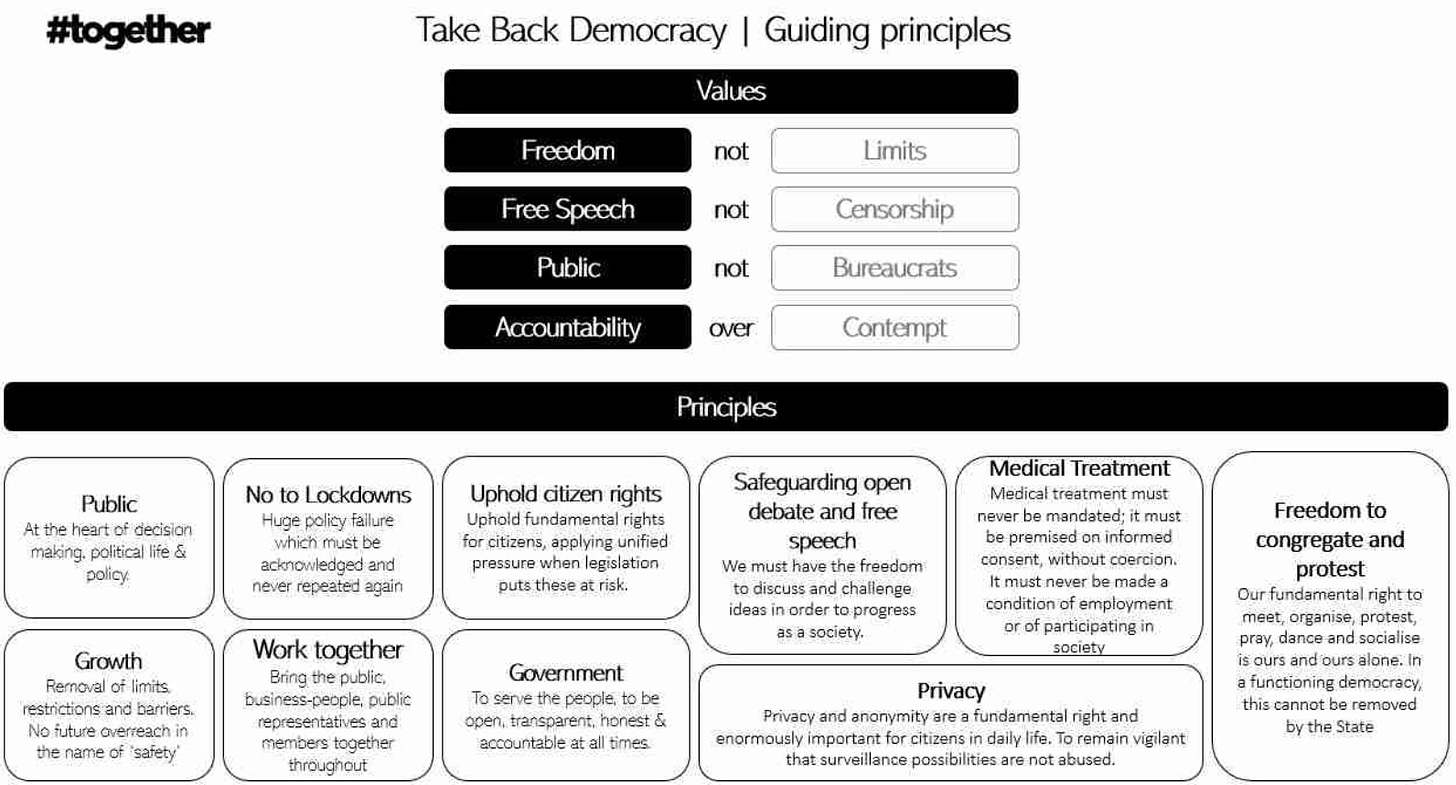

And something even greater may sprout from the small mustard seed of non-conformity: the growth of a movement.

If you haven’t seen this six-minute film of one of the protests in London in 2021, I recommend watching at least some of it:20

To paraphrase again:

The man may begin to do something concrete, something that goes beyond an immediately personal self-defensive reaction against manipulation, something that will manifest his newfound sense of higher responsibility. He may, for example, organize other to act together in defense of their interests. He may write letters to various institutions, drawing their attention to instances of disorder and injustice around him. He may seek out information that contradicts the official narrative and send it to his friends.

Such actions may be considered as elementary revolts against manipulation: you simply straighten your backbone and live in greater dignity as an individual. This may be regarded as one way of living the truth — and gaining an inner freedom which works itself out at a cost. Its most important focus is marked by a relatively high degree of inner emancipation. It sails upon the vast ocean of the manipulated life like little boats, tossed by the waves but always bobbing back as visible messengers of living within the truth, articulating the suppressed aims of life.

He does not envision some political organisation to bring this about, but each person ‘living the truth’ over and against ‘the lie’ in their own spheres of influence of life. This can then develop into a “second culture” — one in which people live free from the fear-mongering of authorities who are plainly not telling the truth, not least because of their conflicts of interest.

This does not mean withdrawal from society but an engagement with it not least by setting up parallel structures — in this case perhaps public meeting places where no-one wears masks — in which the second culture can flourish. These would then point in another direction and, in so doing, establish cultural points in preparation for when the draconian public health policies end.21

It doesn’t take that much of a leap of the imagination to see how this might reasonably be translated to the call for Christians to live the truth (1 John 1:6). The biblical imagery provides the emancipation whilst the Holy Spirit provides us with the courage to live as people of the Truth in the context of all-pervading lies.

I can’t help wondering what Tinker (who died in November 2021) or indeed Havel (who died in December 2011) would have made of the covid era. And e.g. the video featured in this article:

Update — also related:

Dear Church Leaders Archive; some posts can also be found on Unexpected Turns

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered

See also this Anglican Mainstream article

A political dissident since the 1968 Prague Spring, Havel served as the last president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until 1992, prior to the formation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. He was the first president of the Czech Republic from 1993 to 2003, and was the first democratically elected president of either country after the fall of Communism.

Alluding to the order established by Benedict after Rome was taken over by the Visigoths” (in 410 AD)

I have retained the capital O for Orthodox as cited in Tinker’s quotation of Dreher’s book

Quoted from Dreher’s book (p78) in Tinker’s footnote on p165

I wonder how many members of our own congregation wrote to the church leadership urging them to enforce the “covid measures” more stringently, even going beyond what the government required

Most people seem to have forgotten that in Spring 2020 various public health officials (rightly) advised against wearing masks (the clip features Chris Whitty, Anthony Fauci, Jenny Harries, Jonathan Van-Tam, Patrick Vallance…); see also e.g. this discussion of the evidence here

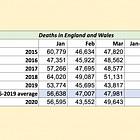

And indeed demonstrating that he is not living in fear (cf. Hebrews 2:14-15), which seems quite reasonable in the context of the fact that, prior to the “covid measures” being introduced in the UK on 23rd March, there were no more people dying than usual for the time of year according to official government data:

The authorities stopped requiring people to wear masks before too many people rebelled (by which time masks had largely done their job insofar as most of the people who were ever going to take covid injections had done so)