Death threats to top scientists questioning the covid narrative in 2020

Stanford professors John Ioannidis and Jay Bhattacharya recall their experiences

Dear Church Leaders (and everyone else)

I thought it worth highlighting the experience of two eminent scientists who, in 2020, were brave enough to speak out about the covid narrative.

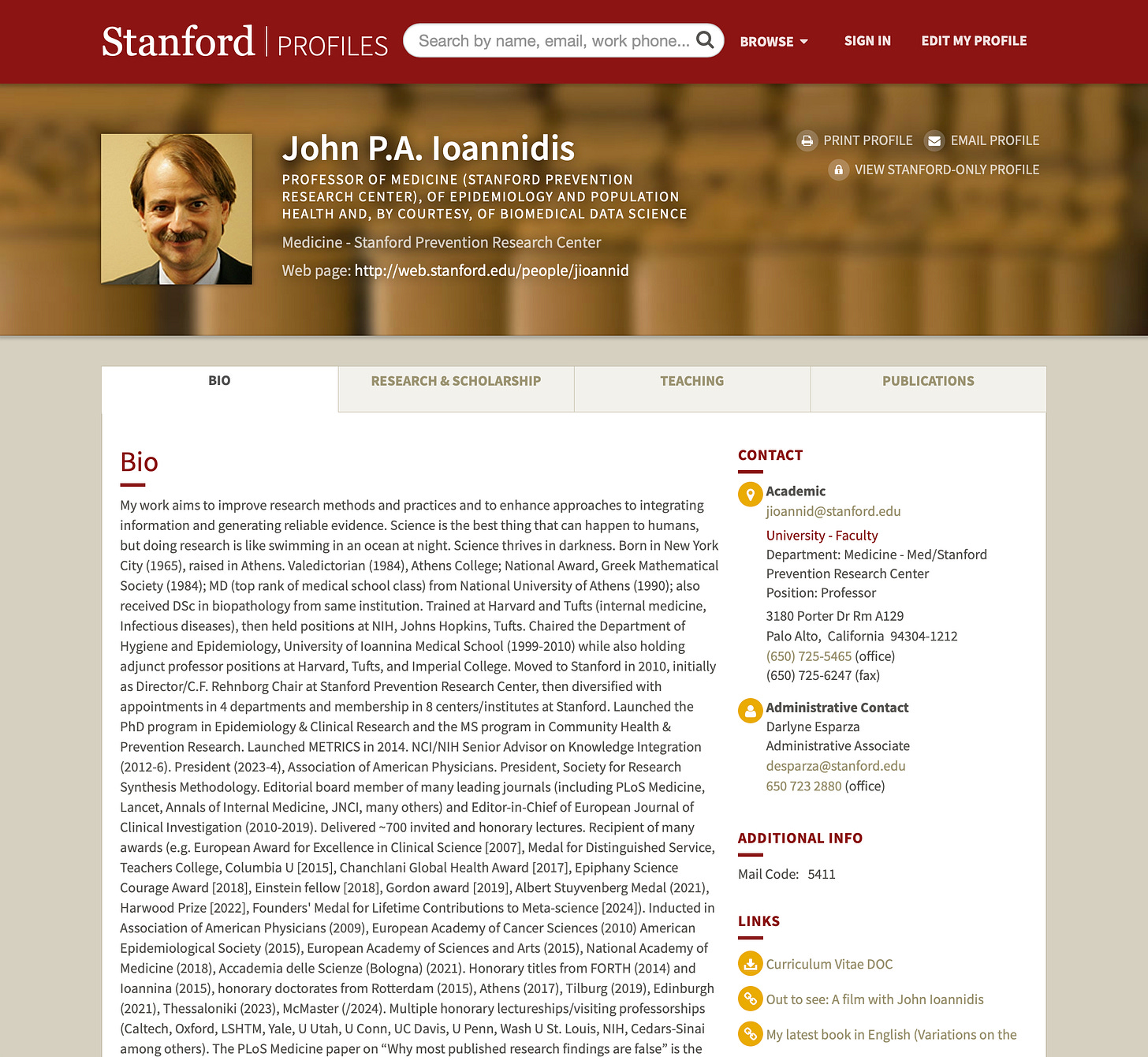

Prof John Ioannidis

Prof John Ioannidis is one of the most cited scientists in the world. He is an epidemiologist based at Stanford, one of the most prestigious universities in the world:

UK cardiologist Dr Aseem Malhotra has described Ioannidis as “the Stephen Hawking of medicine”. But when Stanford University’s Professor of Medicine, and of Epidemiology and Population Health, spoke up in 2020, what he had to say was — to say the least — distinctly unwelcome in some quarters.

Here is Ioannidis speaking recently about his experience (transcript below):

Interviewer: I would like to go back to this climate that was prevalent… and maybe you can describe… the climate… in the scientific debate in the beginning of the corona pandemic [in Spring 2020] when it came to expressing opinions that were… maybe not the mainstream narrative. How was it for you? What did you experience?

Ioannidis: It was a very toxic environment, I think, for anyone who wanted to be involved in these debates, and try to present some data, some evidence, and speculate about what it meant. I think that people had taken very strong positions, and there was very strong polarisation and partisanship, and a sense of ideology running the show. So that was not really the best circumstances for doing science, especially for someone who has no political ideology and doesn’t want to satisfy one narrative or another. Death threats were very commonplace.

Interviewer: Also to you?

Ioannidis: Of course. Both myself and every single member in my family… were attacked in ways that I could never have imagined would be possible to happen… The environment was so toxic that the vast majority of credentialed scientists, who might have some expertise that would be relevant to epidemiology — of course it was a new virus, so no-one really was an expert on this virus when it all started — but at least people who had the background and the credentials that would be relevant… most of those self-silenced…

I’ve heard from so many people, telling me, “John, this is unbelievable. We can’t believe that this is happening. If you are attacked in such a way… if we were to try to do anything or say anything, we would be completely annihilated… we would disappear from the map. And our careers would end. Who knows? Maybe we will be dead?” Everything was possible at that time… the way that the behaviour of the mob and of politicians and mass media and even legacy media and influencers were operating… And I think this meant that even though eventually we got two million people writing about covid-19 [published in the peer-reviewed literature], when we needed it, the best epidemiologists just stepped down.

Most of the people who dictated the narratives had no clue about epidemiology. They may have had some expertise — some of them — in some other fields. There were some very good virologists, for example. There were a few people who had good expertise in some other fields… but not really in epidemiology. I think that epidemiologists were very quickly seeing my paradigm, and other people in epidemiology who were equally silenced and destroyed. They moved out, and and they left epidemiology to people who were not epidemiologists.

Interviewer: What made you stay and and speak about it and publish about it?

Ioannidis: I think that could have been obsession [laughs]. Maybe I was opinionated and wrong. Who knows? But I also felt that I had to try to do the best science that I could, because I thought that it was a major crisis with multiple dimensions, and there were lots of things at stake.

I think that it would be shameful for me to just say, “I’m not going to work on this once I started working, and doing my first studies in the field. It was something that could make a difference if we made the right choices or the wrong choices. So yes, I’m sorry that [laughs] I continue to to do science… Perhaps some of that was wrong. Perhaps other pieces were more correct than others. Who knows? I think that that would take a very long time to arbitrate. But I thought that it was important to try to get as much reliable evidence as possible.

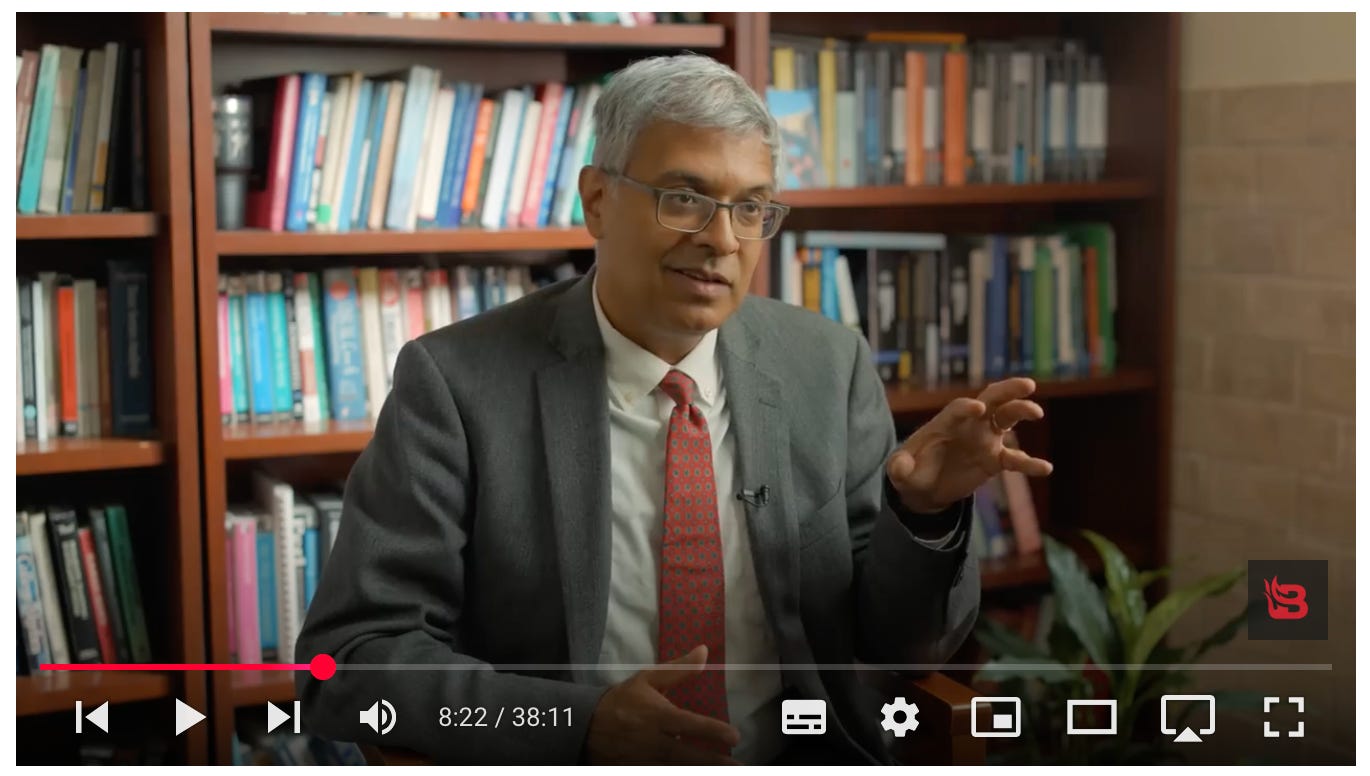

Prof Jay Bhattacharya

And here is another Stanford academic, Prof Jay Bhattacharya…

…speaking last year about his experience (transcript below):

Bhattacharya: I have an MD [US medical doctor’s degree] and a PhD in economics. From the almost the first moment I started doing research I was very interested in infectious disease. My first published paper was on HIV. And because I do economics at the intersection of economics and medicine, a lot of it was about policy. So I published throughout my career a lot of papers on infectious disease.

When this pandemic hit, the World Health Organization… put out a report a estimate in a conference saying that the death rate from this virus is 3.4%.

Interviewer: Devastating if true…

Bhattacharya: Yes, I mean if 3 out of 100 people die from getting this, that is a disaster. Nothing in modern peacetime history has an analog, and it’s going to go everywhere because it’s a virus that spreads very easily. That was really clear from the data early on [that] that was true…

But that number had to be wrong… is what I thought… because I thought back to what happened in the swine flu…

In the swine flu in 2009 the World Health Organization put out an estimate saying… this is a 4% death rate…

The problem was [that] they observed the people that died from the swine flu, but they didn’t observe the total set of people that had been infected. They only saw the people that were really sick… enough to come to the hospital. That meant the death rate was something like 1 in 10,000, not 3 out of 100 or 4 out of 100.

That defanged the swine flu pandemic. It went from this… disastrous thing that's going to kill everybody to… it’s another flu.

Interviewer: The uncomfortable implication of this is that public health officials don’t care about what is true. It’s seen as a virtue to overstate the danger… in other words, to lie about it… whatever gets people to take take the virus seriously…

Bhattacharya: At the time, in January 2020, if you said that, “I’m not sure this number is right… maybe it’s less dangerous than people think… maybe it’s not 3.4%... maybe it’s less than that…” that was seen as a sin… a cardinal sin… It was crazy. It was absolutely outside of my experience… I started getting death threats. I didn’t say one word about economics... It was just pure epidemiology.

In March 2020, I wrote an op-ed published in the Wall Street Journal. The death rate projections based on just simple back-of-the-envelope math could have ranged from 20,000 deaths to millions and millions and millions of deaths.

And we wrote that in the Wall Street Journal piece… we don’t know this… and we called for a seroprevalence study of antibodies in the population

Interviewer: You were just doing what you do, and you had done it before… The scientific process demands that people ask questions, particularly when you see half-baked scare figures that are designed to get people hysterical. But the whole world came down on you because you wrote an op-ed…

Bhattacharya: It was crazy. I would get accusations from friends on campus accusing me of valuing economics over lives. That framing was was so unfair… because if you lock down an economy, which is what we were planning to do… we were talking about doing in March of 2020… you are going to kill people, especially poor people who cannot abide by having their lives disrupted by these kinds of disruptions… their basic economic activities.

You have someone who’s a worker in a market who sells coconuts for a living. And he buys the coconuts… his entire life savings is in the coconuts that he bought. And if he sells… he can then buy more coconuts for the next day and live, and use the rest to feed his family.

You say, “You’re locked down” and that guy’s going to starve. His family is going to starve. You say, “Okay, we’re not going to do trade anymore… we’re going to lock down where all the supply chains are going to get disrupted…” The pointy end of that is some some poor guy in the middle of nowhere whose job depends on this… and now he earns less than $2 a day or something… goes into dire poverty and starves. The decision was always lives versus lives.

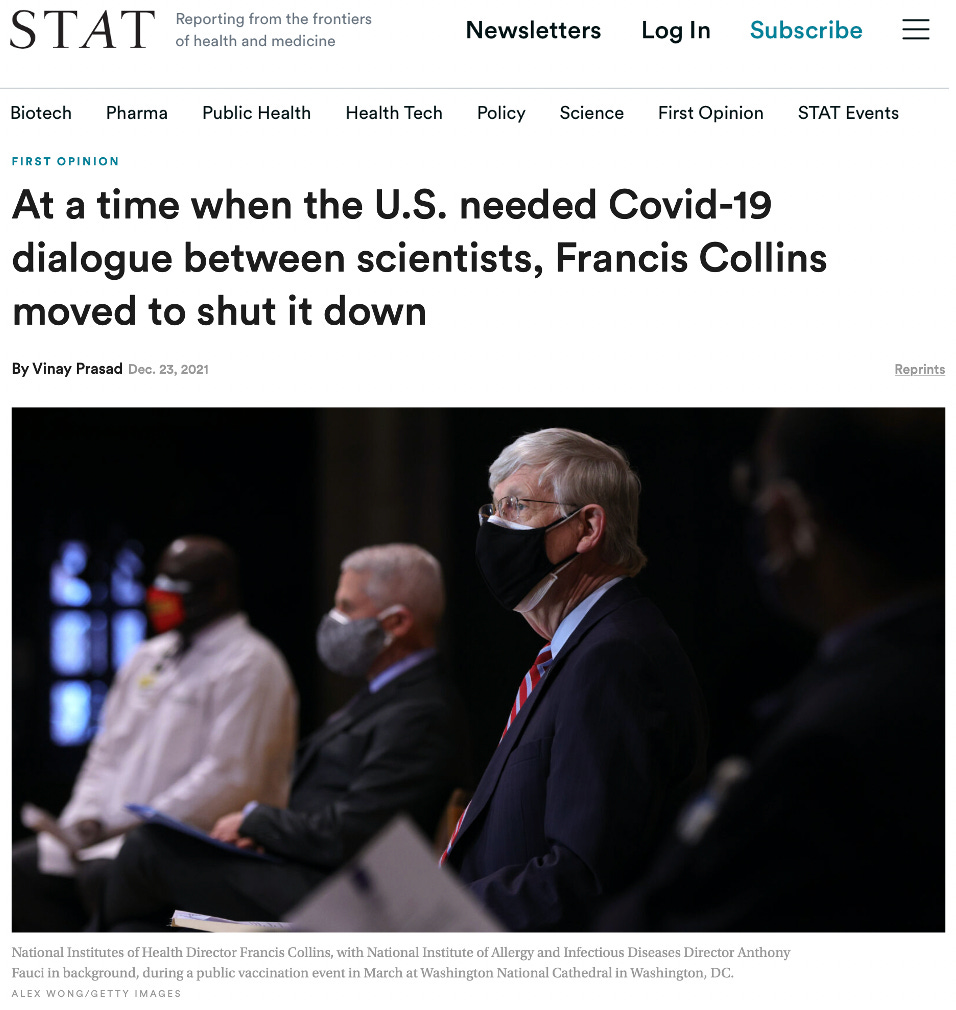

As noted in this post…

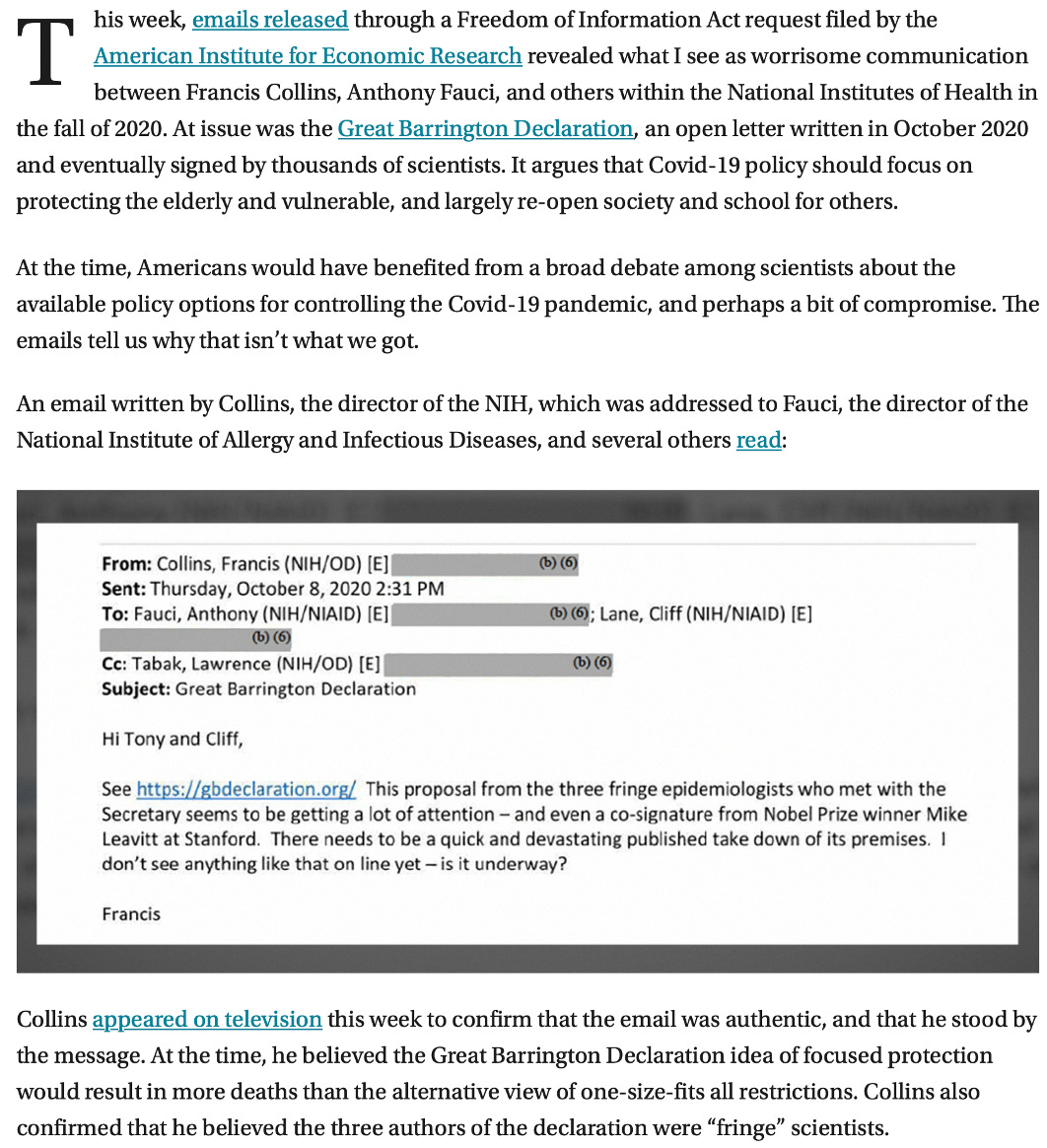

Bhattacharya was one of the “three fringe epidemiologists” mentioned in a 2020 email from Francis Collins…

…calling for “a quick and devastating published take down of [the] premises” of the Great Barrington Declaration:

He was recently appointed as the Director of the US National Institutes of Health:

How times change.

It will be interesting to see how things develop.

Related:

Dear Church Leaders homepage

Some posts, including a version of this one, can also be found on Unexpected Turns

The Big Reveal: Christianity carefully considered as the solution to a problem